We've heard a lot of late about the concept of Gross National Happiness, an export from the strange and lovely Kingdom of Bhutan. Once upon a time, I lived there. An extract from The Nine Horizons (2014)

WE WERE late leaving Delhi. The apron was empty, baking in the heat. The day before we had hired a tuk-tuk, one of those gimcrack three-wheelers in which the driver sat ahead and the passengers on a narrow bench behind. A small two-stroke engine popped and farted below us as we drove to Lutyens’s huge capital, the dome shivering in the heat, the reddish stone hot to the touch. It had been about 47 deg C and the mid-morning sky had been hazy and ill-defined.

|

| Walking at 15,000 ft near Lingshi, Bhutan, April 1993 (Pic: M. Robbins) |

I gazed out over the wing. A small, elderly Russian transport taxied by, complete with gun turret under the tail; it had seen better days. One of a small armada that set out from the former Soviet bloc in those years – it was 1992 – packed with enormous women in old-fashioned headscarves with things to sell and things to buy; a tramp-steamer of the skies, the air around its exhausts distorted and liquid.

I began a conversation with a well-dressed man in the seat beside me. We had the same destination. I would be a development volunteer, sent to Bhutan by VSO, the British equivalent of the Peace Corps. He was a diplomat. He had just finished three years in Kuwait.

“How was that?” I asked him.

He thought for a moment. “Imagine a supermarket in the desert,” he said.

A companionable silence followed. I picked up one of the newspapers that the cabin crew had draped across the armrests, expecting The Times of India. But it was their own national newspaper, Kuensel. A banner headline ran across the front page: GUPS CALL FOR ACTION ON NGOLOP PROBLEM.

I wondered if the Indian diplomat could tell me what a gup was, or indeed a ngolop; but he was dozing. In fact, a gup is a village headman or representative. As to the ngolops, I would find out soon enough.

A cabin attendant passed by, looking right and left to check belts. She was tall—unusually so—and had a broad Asiatic face with very high cheekbones and golden-brown skin, and a curious lack of expression. Her thick black hair was cut in a bob. She wore a lightweight waist-length silk jacket over what looked like a sleeveless wrap. The wrap, called a kira, ran from her chest to her ankles, and formed a sort of tube, leaving little obvious room for movement; it was secured with attractive gold fasteners on her shoulders. Below the wrap was a smart white blouse.

We climbed away from Delhi and across the arid North Indian plain. Lucknow slid below us and we turned gently east. After an hour or so, bright white clouds started to line the horizon to the left; as we neared them, they took firmer shape, for they weren’t clouds. We kept them to starboard a while, then drifted slowly across them, white points and cascades of rock and deep grey-green defiles. They were shrouded here and there by a little cloud—thin as yet, for the monsoon was barely beginning.

Before long, the peaks came closer as we sank into a valley. Later, pilot friends would tell me how, in the monsoon months, they would cruise above the clouds, looking for a hole that was large enough for them to nip through, take a look around, and nip out again in a hurry if there was anything in the way. If there wasn't, they would guess which valley they were in, and guide the four-engined jet through it into the right one so that they could find the airstrip, ready to yank the stick back and pop porpoise-like above the clouds again if they ran out of space, or got lost. (Once above the clouds, landmarks such as Kanchenjunga and the Jumolhari range, and the Tibetan plain behind it, would soon tell them where they were.)

The approach itself was hard. As we began it, the valley slopes moved up towards the plane’s belly. A structure strange to me but clearly a temple of some kind slid below us, wisps of cloud reflecting the sunlight. The peaks were above us now, although we were barely 60 miles away from the blistering Bengal plain. The temple disappeared behind us and we catapulted over the edge of the mountain on which it stood, then dropped like a stone; my stomach flew upward. Later, I would arrive one windy winter's day when the plane would drop into an air-pocket, so shocking us that my neighbour, an urbane and charming acquaintance of royal blood, shrieked and dug her fingers so deep into my arm that it was bruised for a week. Today was smoother. We glided into a deep, rich valley ablaze with agriculture, and as the plane flared and settled, we drifted past a mighty building, half-temple, half-castle, a magnificent riot of white walls, hardwood windows, shingled roof and gilded gargoyles.

We filed down the steps and into the sudden calm of the strange spring morning. There was a small road a few hundred yards away, but nothing moved on it. On either side, the valley was lined with steep slopes, partially forested; the soil between the trees looked light and sandy. It was warm, but much cooler than Delhi, and there was a light breeze. At the far end of the runway, the temple/castle, Paro Dzong, dominated the narrow valley. Nearer at hand was a low wooden terminal. In it we queued before a man wearing what looked like a cross between a dressing-gown and a full-body kilt; the top was loose, voluminous, and I had heard that one could carry six bottles of beer within, kept in place by one's belt. The garment was the gho, the male equivalent of a kira, and was worn at all times, by law, when more than 300 metres from one's house. Across the shoulder was a cumney, was a cross between a shawl and a scarf and was white – unless you were a dasho, which loosely speaking meant a knight of the realm; then it was red. A member of the national assembly wore a purple cumney. The King and his spiritual counterpart, the Jhe Khenpo, wore saffron ones.

We filed down the steps and into the sudden calm of the strange spring morning. There was a small road a few hundred yards away, but nothing moved on it. On either side, the valley was lined with steep slopes, partially forested; the soil between the trees looked light and sandy. It was warm, but much cooler than Delhi, and there was a light breeze. At the far end of the runway, the temple/castle, Paro Dzong, dominated the narrow valley. Nearer at hand was a low wooden terminal. In it we queued before a man wearing what looked like a cross between a dressing-gown and a full-body kilt; the top was loose, voluminous, and I had heard that one could carry six bottles of beer within, kept in place by one's belt. The garment was the gho, the male equivalent of a kira, and was worn at all times, by law, when more than 300 metres from one's house. Across the shoulder was a cumney, was a cross between a shawl and a scarf and was white – unless you were a dasho, which loosely speaking meant a knight of the realm; then it was red. A member of the national assembly wore a purple cumney. The King and his spiritual counterpart, the Jhe Khenpo, wore saffron ones.

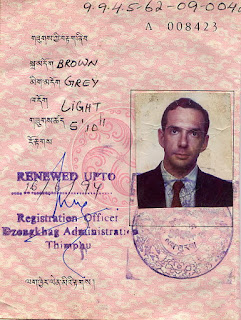

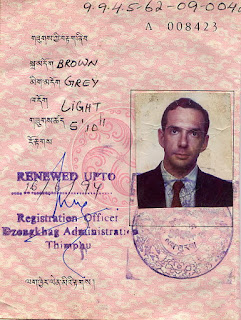

A stamp was thrust onto a blank page; a large, round, purplish-blue stamp, with Tibetan script around the outside, a row of auspicious symbols such as conch shells, and finally, the words GRATIS VISA. SEEN AT PARO. I went out to join the tourists, smug in the knowledge that whereas they paid up to $200 a day for the privilege of visiting the country, I had won that most elusive prize: a resident's permit for the Kingdom of Bhutan.

*** *** ***

One of the world’s smallest capitals, Thimphu had a population of 31,000 then; today, I believe, it is three times that, but in 1992 it had the air of a small country town, the sort you drive through now and then in England when the motorway is blocked and the police divert you. The difference was its dramatic location, in a very narrow valley at 7,500ft; from its edges, steep slopes rose to peaks twice that height, their summits shrouded in the mist and rain of the monsoon season that was just beginning. The lost valley.

I soon explored Thimphu. In truth, there was not much of it then. There was a long main street that started at the top of a hill, and ran for about a mile and a half. It was punctuated by three little traffic islands. There were no traffic-lights; instead, at these three junctions, handsome little wooden pagodas sprouted from the concrete, complete with the appropriate traditional decoration. In each one, at busy times, there stood a smartly-dressed policeman in a blue, Western-style uniform, directing the traffic with stylized gestures, the balletic grace of which was enhanced by immaculate white gloves.

(In the early hours of the morning a year or so later, two friends and I emerged from a private bar a hundred yards or so from the central island, well the worse for wear. The street was deserted. My friends made straight for the nearby island and began to walk clockwise about it as if it were a religious structure, chanting Om mani padme hum – Behold the Jewel in the Lotus. I then leapt into the pagoda and started to direct imaginary traffic with extravagant hand-gestures. After a minute or so we became aware of a white-gloved policeman standing on the corner, his face a mask in the moonlight. We fled.)

The main street was lined with low wooden shops, each with a front partially open to the street. They seemed, for the most part, to sell much the same thing; plastic implements, packets of tea, rather hard soap, chillies, and, for some reason, dried fish – always dried fish, although I never saw anyone buy any. However, Shop No. 9 had beer, while Shop No. 6 was good for potatoes. Here and there were different types of shop; a butcher for instance. And there was a small but very well-kept public library halfway up the street, with an excellent selection of old English-language paperback novels. It was run by a charming young woman who appeared genuinely embarrassed when I returned some books a week late, and she had to make me pay a few pence in fines.

|

| Children near Wangdi Phodrang, western Bhutan (Pic: M. Robbins) |

Nearly opposite was the national bank, which was helpful but not easy to use. One entered from the small car park to find oneself in a dark banking hall with wooden floors; as in India, guards lurked in the gloom, nursing ancient rifles. The banking counters took the form of grilles with tiny apertures, like old-fashioned ticket-offices; behind, one could see shirtsleeved Indian clerks and their gho-clad Bhutanese colleagues writing with pens in huge ledgers. In 1992 there were no computers of any sort in the building at all, so far as I was aware. Withdrawing money involved fighting one’s way to the head of one queue, presenting one's papers, taking a brass counter and then joining the crowd jostling and heaving around the window on the other side, waiting to hear the number on your counter called out so that you collect a pile of rupees (if travelling) or ngultrum, the local currency. This would happen when the clerk on the first desk got around to bringing the record of his transactions across, usually every 15 or 20 minutes. The bank staff were pleasant, but it was chaos.

There were few other shopping facilities in Bhutan. There were one or two shops where one buy could cassettes of Hindi film music, which was popular, or blank tapes, again Indian; these were perfectly good, and not expensive. You could also buy some non-Bhutanese clothes and there were shoes too, but the selection was limited and expensive. A few shops stocked Indian magazines and newspapers, including filmi magazines that reported the doings of Bollywood; these were often in English. Starved of glamour, I bought a few myself. At the time, television was forbidden in Bhutan, but videos were everywhere and Hindi Bollywood movies all the rage. (The video shop sold filmi magazines. One day I saw two monks staring through the window at the cover of a magazine, the headline on which screamed EXCLUSIVE FIRST PIX JAMES DEAN SEVERED HEAD.)

When it came to restaurants, Thimphu was better supplied. The local ones served emma datse, the national dish, made of cheese and burning-hot chilies; I never came to terms with this, but there would also be dhal bhat and perhaps momos. The latter were little dumplings filled with meat, usually pork (occasionally yak, although I only encountered this once, in Sikkim). Or paksha-paa, which was pork (both lean and fat – the Bhutanese made little distinction), with the inevitable hot chilies, served on a large pile of delightful savoury red mountain rice. The pigs had eaten well. Marijuana grows wild over much of Bhutan; Bhutanese people strongly disapproved of its consumption by humans, but used it as fodder. Some schools kept a pig, and small boys and girls in ghos and kiras trotted cheerfully towards the pigpen with armfuls of weed. The pork was excellent.

Western food was also served in a surprising number of places. There were a lot of short-term foreign consultants in Thimphu, and many were not there long enough to get into cooking. The best restaurant, 89, was a little expensive for volunteers but served good food, including excellent chips; I was told that some Irish volunteers, horrified by the soggy chips, had marched into the kitchen and showed the staff how to make decent ones. In 89 you could have a good yak steak in season – that was when the yaks came down to winter pasture just above the town. Yak was a little gamier and tougher than beef, but pleasant enough. On winter weekends I always enjoyed a long mountain walk, or bicycle ride, in the bright, crisp sun, followed by an evening meal of yak and chips at 89. By the time I left, there were several rivals, but none were quite as good.

I often took my evening meals in Benez. This was a small restaurant-cum-bar next to the guest house, on a side-street; it had perhaps eight tables for four, bare and unadorned, with a small but rather cozy little bar at the back of the room. It was run by Dasho. Dasho really was a dasho, or knight; it is an honorific borne by provincial governors and others those who serve the King at high level. Dasho had been a very senior Government official, but he was an ethnic Nepali, and when the political situation worsened in the late 1980s (of which more later), he had to leave his post. So he opened a pub instead. However, he was friendly and cheerful, and I never heard him complain. A short, bullet-headed, bald man in his 50s, he ran Benez (even he did not know where the name came from) with his wife, who sat behind the comfortable little bar in a friendly fug of cigarette smoke.

Benez had plenty of booze. There was bottled beer of different types. The best was Kalyani Black Label from India. Dasho normally had plenty but if he hadn’t, there was always a Sikkimese beer with a green label called Dansberg; it was not as good, but it served. Rarely, one might have to resort to Golden Eagle (or weasel’s piss, as a friend once called it). This had a disgusting soapy taste, but for some reason the Bhutanese liked it. If you couldn’t face weasel’s piss, there was also He-Man 9000, Sikkim's answer to Special Brew. I could not take either weasel’s piss or He-Man so I would sometimes be forced to drink spirits. These do not agree with me, but I would enjoy a Dragon Rum sometimes. This was a refreshing local rum which came into its own in winter, and it was very cheap, I think about 10p a shot. Or one could have Bhutan Mist. This was a truly excellent Scotch distilled locally (the Scots had helped, I think). The local spirits all seemed to come from something called the Army Welfare Project in the southern town of Geylegphug.

Dasho was very hospitable and informal; one might forget he was a Dasho, were it not for the red cumney that he put on before getting into his white Premier Padmini to visit some Government office or other. (I cannot remember him wearing a ceremonial sword, however; perhaps only serving Dashos wore those.) From time to time he would sit and chat. I cannot remember him ever talking politics, and I never asked him to.

But I do remember one conversation we had during the monsoon, not long after I had arrived in Thimphu. It had been a damp, overcast day, and now the rain was sheeting down the windows; I had run here from my flat just behind, my evening reading, a tatty found copy of The Master and Margarita, held close to my shirt. Benez was quiet, one or two people sitting at the back table; Dasho’s wife sat peaceably behind the bar on her high stool, her cigarette-smoke curling into the soft light above her. Dasho sat opposite me, nursing a Dragon Rum. For some reason we fell to discussing local beliefs. Quite suddenly and calmly, he said that he had once seen a dragon.

I blinked. There was no hint of a smile on his face. “When was this?”

“I was doing my military service. In the 1960s.”

“Where?”

“Oh, in the mountains. It was at dusk. Dragons fly at dusk.”

“What did it look like?”

“Strange colours.”

No Bhutanese wishes to see a dragon; they are bad luck, and I sensed that Dasho did not much want to be pressed on the subject. In any case, at that moment my food arrived, and he excused himself; he never raised the subject again. Dasho was a professional man and widely-travelled; he was either telling the truth or testing my credulity, and to this day I do not know which.

*** *** ***

Aside from the centre, there was little to see in Thimphu. Even the majestic Dzong, and the majority of the government offices, were not in the town itself but a mile or two to the north. In fact, Thimphu was a bit claustrophobic. So far I had hardly had a chance to leave it.

I wanted a bike. This was partly for exercise, but also because I like bikes and wanted to explore the area. One could buy bikes in Phuntsholing, the southern border town at the foot of the mountains where they met the Bengal plain. But they were similar to English machines of the 1930s, being very upright and very heavy, with rod brakes and a single gear. I wanted something a bit more modern, or a gearbike, as the Indians called them. I mentioned this to another volunteer, Ken, who said a friend was thinking of doing the same, and he would mention it to him.

I forgot about it until two months later, in September. It was, for once, dry and bright; one of those rare days during the monsoon when it stopped pissing down, the concrete walls stopped turning green with fungus for a while, and the clouds drew back off the wooded hills round the valley, revealing the mass of prayer-flags clustered below the radio-mast on the hill to the west. I had been walking around Thimphu. I was passing Benez in the early afternoon when a horn hooted behind me. I turned to see Ken and a friend in a blue Land-Cruiser. “We got something for you,” said Ken. In the boot was a very smart red-and-white five-speed racing bicycle. The friend, Padraig, had indeed gone to Siliguri in West Bengal to get his Indian gearbike, and, hearing that someone else wanted one, he had kindly bought an extra one. It had cost about £38 (about $55) and was called a Hero Hawk.

|

| A monk admires my gearbike; Thimphu Dzong behind (Pic: M. Robbins) |

I loved it, but it was heavy and needed tender loving care. The first fault I found was that the control cable for the derailleur was too short and would change the gears to low ratio, but would not allow the opposite movement. The cones that held the ball-bearings into the axles were loose, too, and one of the brake hoods moved around. A borrowed spanner and screwdriver proved enough to fix most of this, and I chopped up an old brake cable cover for the gears. The valves, like prewar British ones, had rubber in them. They would not mate with a modern pump, and the Indian adaptors could not cope. Eventually I got a plunger-pump from Siliguri. This consisted of a stainless-steel cylinder with feet that folded out at the bottom; the long plunger was topped by an elegant polished wooden handle. These were much used by rickshaw drivers in India, and were very effective. Lights were another problem. Bhutanese policemen confiscated bikes without lights at night. Someone who was going to Phuntsholing kindly brought back an Indian dynamo set. This lit up the street like a Roman candle but produced far too much power, so that as soon as one got to a certain speed the six-volt front bulb blew, leaving one careering down the main road from the Memorial Chorten in total darkness, wondering how far away the drainage ditch was.

Ken had a bike too. He left Bhutan on it that November. He had been helping in a Phuntsholing factory making plastic piping, but competition from India was fierce, and orders few. Moreover he had lived on the border through the worst of the civil disturbances of those years, and had had an eight o’clock curfew to contend with; there was little enough to do in Phuntsholing anyway. But he stayed for most of the two years, and then decided to go home his way, cashing in his air ticket, and hanging a saltire on his bike, on the crossbar of which he had written BHUTAN-SCOTLAND. With another friend, I accompanied him for the first 20 miles one soft Sunday monsoon morning and we waved goodbye, the saltire waving bravely from his rear carrier as he disappeared into the distance. He covered much of the subcontinent before Iranian visa difficulties forced him to give up the following spring. A young Danish friend was even more ambitious. He bought two sturdy ponies and announced that he was trekking back to Denmark. In the summer of 1993 he set off from Thimphu, and crossed the Bengal plain to the borders of Nepal; but a robbery, and sickness in the ponies, forced him to give up in Kathmandu.

*** *** ***

The bike let me see something of the countryside. Bhutan is one of the most beautiful countries on earth, but there is little view from the Thimphu valley. The surroundings are wooded hills; no snow-peaks can be seen. For that, one had to climb 3,000ft to the 10,500ft pass of Dochula, a long and steep journey; even there, there was nothing to see in the wet season, for the whole country would be shrouded in mist. Alternatively, one could climb on foot up the high mountains flanking the Thimphu valley, reaching a plateau at about 14,000 ft from which there were views of the high Himalayas that surrounded us. But I did not know that then; besides, I did not know the footpaths, and had the brains not to wander around strange mountains on my own. There were bears and boars and mudslides, and tree-roots that could twist your ankle and leave you stranded on a path that no-one might use for days to come.

Still, I could ride to the head of the valley, through woods and along steep roads adorned with chortens, sacred monuments that contained Buddhist relics. After a few miles one reached the point where the last cart-track ran out. Here there was a traditional covered bridge across the rushing blue-white river, the Thimphu Chu, and the beginning of the yak-and-donkey path that led up a narrow gorge to Tibet. Now and then lines of men with pack-ponies would appear at the foot of the valley, laden with simple goods – tea urns, green gymshoes – that they had traded with the Chinese guards on the frontier.

Going south from Thimphu instead led one eventually to the Confluence, where two rivers met; one either turned right for Paro or went straight on towards Phuntsholing and the Bengal plain. However, 20 miles or so out of Thimphu there was an earlier turn to the right, a tarmac road which ran along the Gidakom Valley; narrower than the Thimphu Valley at the latter’s widest, but wide enough for agriculture, a couple of villages and a small lumber yard. The villages also contained the Leprosy Mission, then run by Danes. In the 10 years of its existence it had made such good progress against the disease that it was being run down. The road petered out after about 10 miles, and a track continued to a far-distant lake in the mountains, Bimelong Tsho. I liked riding through the Gidakom Valley; when the sun shone, the buildings shone white-and-brown, and when the chili harvest came, the crop was left drying on the rooves, bright red against the white houses and the deep blue sky. Sometimes one whooshed through a ford and then across the crops that covered the road; they were put there so that cattle-hooves and vehicles would thresh them.

Riding along the main road to the Confluence, I would sometimes pass what looked like public toilets in the middle of nowhere. They were corrugated-iron sheds divided into three cubicles, each one about eight foot wide and about the same depth. Often one would see one of the Indian road labourers hanging around near them, often Bengalis wearing their characteristic shawls. These were their homes, and as far as I could see, the entire family squeezed into these and managed as best they could. I do not know where they got their food; perhaps it was brought up from the plain by their employers, but more probably they had to buy it on the local market like everyone else. I believe they were paid about 15 rupees a day – about 30 pence. In Bhutan, as in any subsistence agrarian economy, there was little labour to spare, and these Indians were essential for road maintenance. The sight of one of these families going slowly and joylessly about their business by the side of the road in the monsoon murk put one’s own troubles into perspective.

*** *** ***

In 1992 the monsoon ran an extra month, right to the end of October. But bad things, too, come to an end.

One Saturday afternoon at the end of the month, I set out on my bicycle, intending to ride up the road towards Dochula. The weather was good, and just after one in the afternoon I rode down the main road to India as far as the majestic Simtokha Dzong, the beautifully-proportioned 14th-century castle about five miles south of the capital. It was here that the Thimphu valley widened out, and Simtokha Dzong commanded a view of it. It was now an ecclesiastical school. When one passed its elegant form, one knew that one had left or entered the area of the capital.

Past the Dzong, I swung round to the left, into a side-turning. This was not quite wide enough for two ordinary cars. In fact, it was the lateral road which connected West and East Bhutan. The most important city of the East, Tashigang, was two long days’ drive along this road. First it snaked its way some 12 or 15 miles up to Dochula, the 10,500ft pass that led out of the Western valleys.

I did not think to reach Dochula. But I suppose I just never stopped. I could feel the warm sunlight on my back, but it was friendly, not oppressive. Looking up, I could see ridges of pine trees against the clear sky, and the road was dusted with pine needles. There was a warm, gentle scent. The road ahead wound upwards so steeply that the next two or three bends were stacked almost vertically above my head, the battlements of the concrete retaining walls clearly visible. There was no traffic, aside from the odd jeep-taxi, and the air felt soft and clear. Below me a valley started to deepen, dotted here and there with isolated farmsteads. Sometime in the late afternoon, I struggled up a last short slope to find the road dividing around a long prayer-wall; there were prayer-flags everywhere, and I realized that this was a place of note. I freewheeled to the left of the prayer-wall and onto a small meadow tufted with weeds. I was exhausted, and it was a moment before I lifted my eyes to the horizon, and saw a sight of such beauty that it was almost beyond the human eye. Below me, looking east, the hills tumbled one upon the other into the far, deep valley of Wangdi and Punakha, 6,000ft below. Beyond that, the ramparts rose again, rows of mountains speckled with fields, meadows and patches of forests, trailing off into a distant blue sky. Then I looked left, and realized that I was looking north into the frontiers of Tibet; distant white pinnacles were shrouded with wisps of cloud against a deepening blue, and nearer at hand was a great snowpeak with a strange, flattened, four-corner summit: Masangang. I was to see it from closer to, some months later, and think it one of the finest in the Himalayas.

|

| Young yak-herders at high altitude (Pic: M. Robbins) |

I stayed there for perhaps an hour, until the shadows rising from up the valley warned me that there was only an hour or so of daylight left. Already a stiffening breeze was chilling me slightly through my shirt, and soon it would be cold. Reluctantly I started down the hill for home. Instead of the two or two-and-a-half-hour climb, I had a 40-minute run down the mountain, twisting around steep, cambered corners slippery with pine-needles and cowdung. The light faded quickly. Every now and then the shadowy shape of a jeep or minibus would appear suddenly around a bend, causing me to heave on the cheap pressed-steel brakes; these barely worked, and I would sometimes cut past with inches to spare. Then a long straight appeared ahead; the brakes came off, and I shot down it at perhaps 40 miles an hour towards the shapely shadow of Simtokha Dzong, looming above the road against the last of the light. The paddy-fields of the Thimphu Valley drifted into view, and then, as I rounded the corner, there was Thimphu, looking more than ever like a woodcut of Middle Earth with the first lights glimmering and the white and gold curves of the main monument, the Memorial Chorten, clearly visible. I shuddered to a halt as I reached the main road, and I think I was laughing.

*** *** ***

Bit by bit, I was absorbing the Bhutanese way of work.

It was deeply hierarchical. Confronted by a Minister, a lower member of staff – even quite a senior one in his own right – would make the appropriate gestures with his cumney, the white scarf across the shoulder. I have already mentioned that these had different colours for certain rankings; white for an ordinary individual, blue for a member of the national Assembly, red for a Dasho, and saffron for the King himself and the Jhe Kenpo. There was another as well – that of the Dzongrub, or deputy Dasho Dzongda; his cumney was white, but edged with a pattern. All this enabled people to know where they were in the food-chain. Although I sometimes heard some of the more Westernized Bhutanese grumble about one or two of the restrictions they faced in their country, I rarely heard complaints about this; perhaps they felt that as long as everyone knew their place, everyone had a place, and this was no bad thing in a time of change. I would have found these formalities hard to perform, but by wearing Western clothes, I kept out of the Bhutanese power-structure, and was not expected to.

People’s beliefs also dictated office behaviour to some extent. A pregnancy went unremarked. I found this curious at first, as the Bhutanese are not prudish, and do divorce and change partners, at least up to a point. In fact it was not prudery; to mention a pregnancy was to attract the attention of the evil eye. Another puzzling habit was the burning of papers. Between the huts occupied by the ministries and departments were small, open-sided concrete bins, about two feet square. These were usually either filled with paper, or smouldering gently. The Tibetan-derived Dzongkha script is sacred, and must not be thrown away; it must be burned (it then ascends to Heaven). So any memo, duty roster, canteen menu or other routine item was dealt with in this way.

|

| Onlookers at a festival in Thimphu (Pic: M. Robbins) |

Fortunately Dzongkha was not used for everything. The script had about 80 basic characters, with perhaps three common mutations for each, and the grammar and orthography are challenging. Typewriters for the script existed, but if someone was well-educated enough to understand Dzongkha, they also read English. (The only exceptions were the monks, who generally spoke Dzongkha alone.) After suggesting, several times, that we ought perhaps to be producing material in Dzongkha as well as English, I was quietly but frankly told that Nepali would be at least as much use and English even better. I have since wondered: would it have been sacrilegious to delete a file written in Dzongkha? Would one have had to transfer it to floppy, and burn that? (Ordinary rubbish, however, was disposed of with less care. Bhutanese people worried little about rubbish. The town government did, and big green steel cylinders had recently started to sprout all over Thimphu decorated with the legend USE ME. For this reason, a rubbish bin was known in Bhutan as a useme.)

There was a wider ambivalence amongst the Bhutanese about development. It seemed, to many, to challenge their unique culture and polity, and send them the way of the other independent Himalayan Buddhist kingdoms (they were thinking chiefly of Sikkim). But it would also make them better-placed to resist the cultural assault from the Bengal plain—which many regarded as a greater menace.

It would be easy to see Bhutan as quaint, charming; Shangri-La – but in Bhutan, as everywhere, you patronise at your peril. Bhutan had just passed through a year in which the Southern problem was as bad as it would ever be.

People of ethnic Nepali origin had long settled the southern flanks of the Eastern Himalayas, where Bhutan tumbled down to the plain. In the early years of the 20th century, the building of the railway through Assam brought more of them to the region, to work on its construction; when it was done, more settled on the fertile, underpopulated southern slopes, raising crops such as cardamom. By the late 1980s they constituted a large part of the country’s population, to the extent that could, it was felt, call into question Bhutan’s existing identity. The Bhutanese reacted with a series of measures, including the compulsory wearing of national dress and a strict nationality law. Tens of thousands of ethnic Nepalis, not all of them resident in the south, lost their citizenship, or felt discriminated against to the extent that they felt they should leave. In the year or two before I arrived, it was not unusual for a colleague or acquaintance to simply pass out of view. Months later one would hear that they had been seen in Kakarbhitta, the small town just inside Nepal where the ethnic Nepalis were sheltered in refugee camps (they were not Nepali citizens either). Few suffered any worse fate, but there was some violence, and an insurgency movement in the south (these were the ngolops I had seen in the newspaper headline). At the time I arrived there was still an 8pm curfew in the southern border town of Phuntsholing, and the tension was palpable.

In fact, by 1992, the very worst was over. But we had no way of knowing this then. The teaching volunteers in particular found the situation difficult; they had seen many of their pupils forced to leave the country before their education could be completed. Some went to visit the camps to see their ex-pupils. The Government must have known this; Bhutan was not a police state, but it was inconceivable that they did not have information from the camps. Other volunteers served out their time in Bhutan, and then went to work as volunteers in the camps for some months. I met one, a good friend, in Kathmandu in December 1993; she had been working on a poor diet with little support and looked thin and ill.

In later months I got to know several younger Bhutanese in their 20s who were members of the Royal Family; although not of the King’s immediate family, they knew him and were profoundly loyal. They were warm, able men who enjoyed a few beers but also worked hard in the Thimphu ministries, and were generally respected by other civil servants. (The King, who lived simply and worked hard, took a dim view of quasi-Royal freeloaders.) They always encouraged me, but we had completely opposite views on the Southern problem. Once or twice I was asked what I thought about it, and I replied that I was not about to tell the Bhutanese how to run their country; but that I believed in human rights, and I did not like it. I said that they must not press me on the subject; they accepted this, and we talked of other matters.

In any case, what to a Westerner was a debate about human rights was to a Bhutanese an argument about their national survival. I realised this more fully when I travelled to Sikkim with a friend at the end of 1993. Gangtok was cheerful and lively – in fact, I liked it; but every face seemed to be Nepali or Bengali. The Bhutanese had told me that the former people of Sikkim, the Lepchas, now accounted for just 15% of the population. Our visit was far too brief for us to know if this was true. But from what little we saw, the Himalayan kingdom which had once existed here had left little trace. It was easy to understand the rising tide of panic in Bhutan, if harder to accept the civil-rights violations it had engendered. In any case, as someone who loved Bhutan but had no stake in its future, I did not feel I had anything useful to say about all this; and perhaps I still don’t.

*** *** ***

Of course, there was a Bhutan beyond Thimphu; in fact, most volunteers worked in it. They were mainly teachers. (Bhutanese schools taught in English, although the children did learn Dzongkha.) For the first year, the volunteers stayed in one village and taught. This first year could be an inspiring experience, but the volunteers were very much on their own and strength of character was essential. It is an experience well described in Beyond the sky and the earth (Macmillan, 1999), by Canadian volunteer Jamie Zeppa, who taught in an isolated community in the east of Bhutan. Jamie, a talented writer who also later produced a very good novel, went on to Sherubtse College, teaching the young people who would become Bhutan’s civil-service elite.

|

| Ploughing near Punakha, Central Bhutan (Pic: M.Robbins) |

This was unusual; more often, the teachers (who were mostly but not all women) became resource teachers for their Dzongkhag, or province, and travelled much of the time, supporting and advising their Bhutanese colleagues. None of the Dzongkhags were easy to travel in, but some at least had a sealed road running through them, and the teacher could use a Bajaj (an Indian Vespa) for at least some of their journeys. Others had virtually no roads at all. These included Lhuntse in the north, and the most notorious of them all, Shemgang, a vast Dzongkhag that stretched from the centre of Bhutan to its southern frontier. It was the least-developed region of Bhutan, as remote as even the very high land close to Tibet. Apart from roads running on the northern and western borders, Shemgang had no tarmac at all.

The resource teachers could spend as much as seven out of eight weeks walking between villages, coping with drunken porters, isolation and the monsoon rains. Not least of the hazards was the local firewater, arra, which was always offered, often first thing in the morning; more than one teacher awoke to find a tumbler of water placed thoughtfully beside their bed by their host in the village, and gulped it back, giving an explosive start to the day. Etiquette, particularly in the east, demanded that one do everything possible to force arra on a guest; cover the tumbler with your hand and the arra was poured over it by a giggling host. But at least this set one up for the leeches, of which there were many in the forests under about 5,000 ft; these waited in the branches, sensed movement and dropped onto the flesh of the traveller below. Less often, there were Himalayan black bears. Bears have no wish to meet humans, and if they do attack it is normally because they have done so suddenly. So those who walk on their own in the mountains often carry bells attached to their waists to warn animals of their approach. But sometimes bear and teacher did meet without warning, although they never did each other any harm as far as I know.

And besides the physical dangers, there were blows to one’s ego. One English ex-headmistress told how she had been helped on with her kira by the lady of the house in which she was staying. “Oh, Madam,” she said, shocked, “you have hairy legs, like a buffalo.” On another occasion she strode into a remote village with another volunteer and, the next morning, attended assembly at the school. The headmaster decided to deliver a lecture to the Bhutanese teachers on the need to make sacrifices for the country’s future. No-one, he said, should be afraid to walk for days to the remotest schools. He indicated the two Englishwomen. “They can do it,” he said, “and they are fatty types.”

I was less adventurous. But one spring an American United Nations volunteer and I decided to cross much of the country on the lateral road, using his motorbike. This journey required a permit and I made several trips into the ornately gloomy wooden interior of the main administrative centre-cum-castle, the Dzong. This involved finding the tiny cubby-hole where the lady in charge of internal visas worked, crouched over a typewriter before a painted background of mandalas, wearing a shiny silk waistcoat over her blouse and kira.

One Saturday morning in early May, Tom appeared at my flat with the little trail bike. It was already laden with bags, Tom’s modest luggage and the bits and pieces he was taking to other volunteers along the way. I added my own bright-green rucksack, with washing things, a towel, a change of clothes and nothing more. But when we had finished securing this to the back of the bike with bits of elastic, there was far more luggage than bike, and I wondered just how far we were going to get. There was a slight slope down to my door. Tom revved the engine and tried to move away, but the bike stalled. Exasperated, on the third attempt he revved it high and banged in the clutch. The little bike took off as if it had been stung, the front wheel rising high in the air, Tom hanging onto the handlebars in an effort not to slide arse-first into my rucksack. After what seemed to be some minutes, the front wheel bashed down on the surface, sending little spurts of gravel into the still morning air. “OK, get on,” said Tom. As Tom pulled away, I put my foot on the right footpeg. It broke. But we made it across Dochula (and later Pelela, which was 12,000ft). Tom handled the bike with great skill. A laconic, rather easy-going man, he worked with the Thimphu city government.( Like Jamie he was a good writer – extraordinarily good, in fact; he would later produce In His Majesty’s Civil Service, a book of short stories, each a deeply observed picture of some aspect of Bhutanese life.)

At the end of the first day we swung off the tarmac road onto a wide gravel track. At first, this climbed gently; but it became imperceptibly steeper, and the little fist of the single piston slammed up and down as fast as it would go as we crawled up in first gear, just fast enough to keep a straight line. As we climbed, chasing the last of the afternoon’s sunshine up the mountain, we could see the hillsides to the north and east. Just as the last patches of sun slipped away, we struggled round a last bend to find the village before us. It really was a village, with the houses arranged around a broad central area; many Bhutanese houses stand alone in their paddies, the neighbour just within hailing distance. A few people milled about, mostly the very young or old; it was a busy time in the farming calendar and everyone who could work was in the fields, using the last of the light.

|

| Village near Wangdi Phodrang, Central Bhutan (Pic: M.Robbins) |

The bush telegraph had warned the volunteer teacher in the village that we were coming, and she stood waiting for us. She helped us unload the bike and we walked together through the twilight fields around the village. Here on top of the mountain, there were plenty of trees, and the fields looked prosperous. Our friend showed us a small pit full of rocks; this, she explained, was where the women of the village came to bathe. The rocks would be heated until they glowed and flung into the water, making clouds of steam. She described lying back in the water and watching the stars swarm across the coal-black sky above the steam. And she talked about her village, which she swore had been painted by Brueghel the Elder. “You see, everyone is there in the square,” she said, “and they work and they work and they have so much to do, and no-one seems aware of anyone else.” Years later, standing before the Brueghels in the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, watching the wheelwrights and the coopers go about their business, I suddenly remembered my friend and her medieval village on top of its mountain.

That night we climbed the outside ladder to eat in the house of a neighbour. We sat on the floor before the bukhari, the wood-burning stove; this was lighted for cooking, and was kept burning, because at 8,000ft the air soon cooled when the sun went down. It was quiet in the room. There was little furniture, for the Bhutanese do not use much, just short low benches with padded tops that can be removed so that the space within can be used for storage. In fact there always seemed something spare and spacious about the Bhutanese room, despite the thick walls and the small windows. Spare but not austere, for the walls are covered with all the symbols of Buddhism, from conch shells to images of the saints; the outside walls will often bear fertility symbols in the shape of a giant penis. A dog came padding through the next room. The Bhutanese seemed to like dogs, and, as Buddhists, are in general respectful of other living things. The dog stretched its forepaws over the raised lip of the doorway; all rooms have these. They are designed to prevent small malevolent spirits entering the room. The dog dragged its hind legs across the lip. Our host handed us tin plates piled high with red rice. I tried to remember the dos and don’ts of the Bhutanese household. Do not whistle; this will attract evil spirits. Do not call someone’s name at night; the same spirits will remember it. We finished our rice and drank suja, or butter tea. “You may go now,” said our host kindly, meaning nothing more or less than what he said; and we scrambled down the ladder in the dark and rolled ourselves in our sleeping bags and I fell asleep nearly at once, the sound of the little steel fist buzzing in my ears.

In the morning the villagers asked us in to see their temple, which they were redecorating; in Bhutan, one visits a village temple strictly by invitation. We climbed a stepladder up the side of a small, square building, and found ourselves in a small, square white room. On the wall, there was a half-completed painting of a terrifying deity. What had yet to be painted, had been neatly sketched out on the white wall in pencil. The deity was identical to those seen thousands of walls in Bhutan and elsewhere in the Buddhist world, often many hundreds of years old. The paintings, like the village itself, were much was they would have been in the Middle Ages. I was suddenly struck by the fact that these older deities must also once have been half-sketched, half-painted, the artist taking a break, perhaps, for suja, or showing his work to a visitor, a few chickens running about in the yard below, a sloshing sound as a housewife threw the slops from her balcony, the cry of a child that has fallen over, the creak of a door in the middle distance; all of it a thousand years ago.

We travelled on for several days. I especially remember a village south of Trongsa in central Bhutan, where we stayed with another volunteer teacher. The village was halfway up a very deep river valley; the scattered houses and paddies on the far slope were at least three miles away, tiny features on a massive hillside that bulked left and right as far as the eye could see. No road ran down the valley on the other side. The valley was so deep that to have reached them on foot would have taken five or six hours, even if one had no trouble crossing the river. Indeed, the landscape was on so vast a scale that, from our friend’s garden, one could see three, four, five villages at each glance, all of them distinct communities, and two or three miles at least from its nearest neighbour. I wondered how much each one knew of the other. The Bhutanese are not insular, but they are very self-contained, and I imagined them living quietly over there, unconcerned with the pinprick headlamps they must have seen now and then on the road across the river.

The sides of the valley were very lush. Parts were wooded, especially higher up; others were covered in scrub, but much of it was carved into intricate terraces. It was spring; transplanting was not far away, and the paddies were a vibrant green. The houses between the paddies were bright white with new paint and seemed to sparkle in the sunshine. Here, high above the Mangde Chu, the steep rushing river that roared out from the high snowpeaks a few miles to the north, I knew I was in a living, breathing landscape, its fabulous beauty enhanced rather than spoiled by a rural economy that is at one with its environment, not struggling with it. It was a memory that would return to me again and again in later years in the Middle East, where man seemed to have taken on his surroundings and fought them to a bloody standstill. I had always believed that, at base, people of different cultures were the same in their feelings and aspirations, however different their beliefs and ways of life might be. In Bhutan I realized that this is only true up to a point.

That evening our friend, pottering in the house as the sun went down, sent us to the local shop for weasel’s piss. The shop functioned as a bar as well of course, so we had a couple of nips each of Dragon Rum. In the house we drank some of the weasel’s piss. Then we went to a party given by friends of our friend’s (actually the whole village was friends with her; after all, it wasn’t very big). Twice we went out to get more weasel’s piss but then we found we had drunk every bottle in the village, so we switched back to Dragon Rum. I can remember sitting on a log outside with the teacher in the warm spring air. Later we had an argument. I cannot remember what it was about. Both she and I had hot tempers and we were still screaming at each other when we got back to the house in the early hours of the morning. We had come along the road, and had to negotiate the steep slope down into the yard; it was pitch-dark, and she grabbed my arm. I think she was trying to help me find my way. Or perhaps she was trying to throw me in the mud. In any case the two of us collapsed in a heap at the foot of the slope, rolling on top of each other. Somehow we all got up the ladder without breaking our necks and she disappeared to bed, slamming the door behind her.

Early the next morning we loaded up. We had been here two days and the bike seemed unfamiliar. Together we strained to push it up to the road. Tom checked the luggage straps and climbed on. He pumped the kickstart a few times and then the engine chuckled into life with a whiff of undigested petrol. “OK, get on,” he said wearily. He had drunk less than I the night before but he looked tired. Our friend stood beside us, kira and blouse still immaculate. She looked sad, or perhaps she was just hung over. “Please be very careful on the way,” she said. She kissed us each gently on the cheek, and stood for a moment as we pulled away. The wind cut through the Dragon Rum fumes and I felt a little better. I glanced back, to see her turning away down the slope.

Six months later I travelled to Bumthang in Central Bhutan for a conference. There was no bike this time, just a big comfortable Land-Cruiser. It was autumn by now, a bright day, the oaks on the passes a brilliant orange. On the way back to Thimphu we stopped for lunch in Trongsa, in a hotel where foreigners often stayed or ate; it was run by a Tibetan woman whose warmth and kindness to volunteers were legendary. As we left I saw our friend. She was standing with a friend by the side of the road; I think they were looking for a lift. We talked for a few minutes, then it was time to go. On a sudden impulse I dug into my luggage and found a pot of local honey that I had bought the day before. I ran back to her and handed it to her. We laughed and kissed each other goodbye and then I got back into the car and we drove away, leaving her standing outside the hotel. A few weeks later I left Bhutan forever and I never saw her again.

*** *** ***

I loved to walk in the mountains around Thimphu. I rarely did so alone; there was no mountain rescue service, and bears lived in the forests on the lower slopes. My usual partner in crime, Piet, was a Dutch consultant in his mid-40s with a frightening ability to walk and cycle long distances in places that were inaccessible, dangerous or just plain odd. (He still does. Currently back in Bhutan, he has quite recently cycled across – and beautifully photographed – Mongolia and China and, incredibly, Ladakh.) Piet, his American wife Melissa and their friend Linda, herself a former volunteer, were endlessly hospitable. Long walks often ended with a beer on their veranda overlooking Thimphu, the lights of the town coming on as the shadows spread up the mountainsides from the valley floor.

|

| A yak skull guards a winter pasture above Thimphu (Pic: M.Robbins) |

Usually with Piet, sometimes with Tom, and often with other friends, we would set out on a Saturday morning at maybe nine, and by lunchtime we could enjoy our sandwiches at 14,000ft above the monastery of Phajoding, its golden rooves glittering in the sun, and Thimphu spread out like a map 7,000ft below us. Now and again we would press on further and higher, to a moorland where, in summer, there would be herds of yak hundreds strong, and the horizon was flecked with snowpeaks: Bhutan’s highest mountains, Jhumolhari, Jichu Drakey and Tseringgang. In the far distance, on the borders of Nepal, West Bengal and Sikkim, one could just make out the long form of Kanchenjunga. (In December 1992 I went to Darjeeling, and got up far too early one morning to watch the snowfields on the mountain catch fire as the first rays of the sun slid over Tiger Hill to its east and the first light crept slowly into the deep valley below.)

We walked and we walked and we walked, and from October to June the weather was, for the most part, with us. Even in winter, although the early mornings were very cold, the sun soon warmed the back of your neck, and the light was clear. There were few clouds. But it was as well to be home before sundown; the temperature dropped quickly then. On one occasion, we were caught by a rare snowstorm. It was a lesson we did not forget. March brought the spring, and soon the rhododendrons began, appearing first just above Thimphu and then moving higher, so that they could still be seen in June if one cared to climb a few thousand feet. It was worth it. They were astounding. But by this time the clouds were starting to build up in the afternoons, and in July the monsoon broke. We continued to walk, for it rarely rained before midday. Now and then it didn’t at all. But usually a monsoon walk was a wet business, with muddy boots and wet cagoules dropped in heaps at the end of the day.

A monsoon walk had its gifts. By the time the cloud started to build at midday, one was above it, and could look down and watch it boiling up out of the Thimphu valley, smothering the little town below. One afternoon we reached the ridge above Phajoding to find that there was little to see. Cloud had closed in below us and we were looking down on its topside, but now and again we could see the mountains across the valley. There was a higher layer of cloud above us, and it was raining slightly. We sat and ate lunch, huddled in cagoules, and the weather closed in around us so that after a few minutes we could see barely 20 yards; beyond that, in all directions, all was white. Then a patch of grey appeared in the clouds below us, and widened slowly. Eventually, the little city of Thimphu could be seen, neatly delineated by the hole in the cloud. Everything else remained white. So there was a city, floating like the centre of an unfinished canvas. It remained there for several minutes before the sky reclaimed it and we were left, marooned, above a sea of white.

*** *** ***

I was happy with very little then. The only possessions I had in Bhutan that I owned were my Indian bicycle and a cheap stereo cassette-deck. Together they had cost me perhaps £75. Both kept going wrong. I spent much of my time tinkering. When I was not tinkering, I was reading something from the well-stocked public library. Or sitting in Benez, either chatting to someone or reading quietly. My whole life was in Thimphu, for I owned little in England, and had no money in the bank. (Indeed, when I had left, I had been some £125 in debt, but my friend, who was an accountant, told me I was entitled to a tax rebate that would pay this off. Three weeks after I arrived in Bhutan I received a cheerful note from London. “I have recovered the sum of £130 from the Sons of Satan and have given it to those leeches you bank with,” it said.) My only income was my salary from the Department of Agriculture; about £60 ($100) a month, it was just enough. As I was 35 when I arrived in Bhutan, and most of my contemporaries had bought houses and started families, all this should have worried me. It didn’t.

My work at the Department had gone well, and I had extended my two-year posting for six months. I liked my Bhutanese colleagues a great deal, and was proud of the communications unit we had founded for the Department, the newsletters and booklets we had produced, the little darkroom I had set up with Indian equipment, and our desktop publishing (quite new even in the West then).I also admired Bhutan's balanced and careful approach to development. I still do.

But I could not stay in Bhutan forever. The Government did not like foreigners to hang around when their job is really done, and with good reason; it was becoming clear that my colleagues could soon do the work themselves, and of course they would want to. I had already been interviewed for a new job (in Aleppo; but Syria is another story). In December 1994 I disposed of my few belongings. My cassette-player was badly worn, so I gave it to a Bhutanese friend who I knew could fix it. I left a box of tapes and a few books in the office. I returned my books to the library; those that were mine, I gave away. I threw all the filmi magazines into the useme a few yards or so from my flat. (When I went into Benez half an hour later, I found the customers cheerfully reading them.) At last I had no more than I could carry on my back. That was how I came to Bhutan. Now I left with less.

Two days before departure, I closed my little flat and took my rucksack up the hill to the big house where Piet, Melissa and Linda lived. The day before I left, Piet organized a leaving party. Being Piet, he organized it in a yak-meadow at 11,000 ft. We walked for four hours to get there, in a snowstorm. We huddled round a fire and drank lots of beer and rum. Then a Japanese friend drove me back to Thimphu as darkness fell on my last day in paradise.

An American friend, Ed, was flying the plane the next day. So he asked me to join him on the flight deck. The tall stewardess strapped me into the jumpseat, and I looked out through the clear, bright air at Jumolhari, Jichu Drakey and Tsheringang as they slipped behind us, revealing the brown shadow of the Tibetan pleateau behind them. We crossed North Bengal, with Darjeeling and Kalimpong slipping away in their turn; passed the towering walls of Kanchenjunga; and then there was another mountain to starboard, its summit streaming snow. “Take a look, huh,” said Ed. “Most people won’t get that close to Everest.”

At Kathmandu I walked away across the tarmac wearing a huge cowboy hat a friend had given me. Ed leaned out of the window. “You take it easy,” he called. “You take care of yourself, OK?” And several other people seemed to be yelling and clapping and cheering, but I could barely hear them for the noise of a door and the crash of steel bolts as they slammed into place forever.

Jamie Zeppa’s book Beyond the Sky and the Earth: A Journey into Bhutan is available in hardback and paperback and for e-reader; her novel, Every Time We Say Goodbye, is published by Knopf in Canada. Tom Slocum’s In His Majesty’s Civil Service was published privately in 1996 and can be found on Amazon.

A longer version of this piece can be found in Mike Robbins's collection of travel writing, The Nine Horizons, which was published in 2014 and is available as a paperback, as a Kindle download and in other eBook formats.