Why do we study it?

It was the

last lesson of the day. Mr Balcombe donned his mortarboard and his gown. White

chalk powder adorned the latter. This was from the Latin class after Assembly;

he had flung the blackboard wiper at Brockley Minor, an especially dense member

of the Remove who failed to conjugate the verb manere. The missile had

missed, hitting the rear wall of the classroom with a dull thud and releasing a

white cloud that caught the morning sunshine that streamed in through the high

sash window. “Since you cannot conjugate manere, you will, er, remain

in detention after supper this evening,” said Mr Balcombe, delighted with his

own wit.

He also had

the overpowering sensation that he had met him, at least briefly, years before.

“I

understand, Balcombe, that his lessons are a little – er, unorthodox,” the

Headmaster had said before lunch. “Sir Rodney Bush and one or two others have

enquired. It seems their boys have mentioned them.”

“The lessons

worried the boys in some way?” asked Mr Balcombe. He sipped his sherry.

“Well, no,”

said the Headmaster. “They said they enjoyed them. So you might sit in on a lesson

or two and check he is teaching properly.”

If Mr

Lawless thought this unusual, he gave no sign of it. Mr Balcombe seated himself

by the window and watched his colleague write on the blackboard, then turn to

the class. On the board he had chalked:

EMERGENCE

And in a

smaller hand:

Of what?

When? Why? What happened? Then:

DID WE

KNOW?

“Last week

I asked you to consider these, with reference to a change, or incident, of your

choice,” said Mr Lawless. “You have written essays. Bush. Tell us of an age and

its emergence.”

“I thought

of the Black Death, sir,” said Bush.

“Very good.

The emergence of – what? A disease yes, but of what new phase or age?”

“Men asked

more for their labour, sir,” said Bush. “So farming changed.”

“It did.

The Acts of Enclosure, the arrival of sheep – what is emerging, Bush?”

“A prosperous

new world, sir.”

“Indeed.

For some. But as the plague raged, none knew of that; only of the terror they

felt. So. Thorpe. Your essay. Most original. Tell the class what emerged.”

“The age of

steam, sir. Newcomen’s engine.”

“Yes. But

did we know what was happening?”

“A few

Cornish miners may have done, sir.”

“Exactly.

The rest did not know,” said Lawless. He was walking back and forth before the

class, stroking his chin. “That was in the 1690s. Two hundred years later, we

cannot imagine life without the train. The cotton mill. And now the Dreadnought.”

He looked around the class. “Now, someone – Bush, I think – asked me earlier

this term why we study history.” He looked at a spotty youth at the back of the

class. “Grimbly, tell me why we study history.”

“So that we

can spot it happening, sir?”

“Precisely,”

said Mr Lawless. “Tell me, everyone; is an age emerging today? Now? In this

year of our Lord nineteen hundred and twelve? And how shall we know?”

No-one

answered, for there was a hullabaloo from an adjoining classroom; and then a

noise appeared from outside, a clawing, ripping sound, and doors banged as boys

poured through the corridors and out onto the terrace that led to the playing

fields. All turned their heads upwards, eyes shielded against the late

afternoon sun; the noise grew louder and a shadow crossed the First Form

cricket pitch and there it was, an assemblage of sticks and wires and stretched

doped linen, a trail of black smoke behind it, drawn across the sky by two

spinning discs that caught the sun. It drifted past them, perhaps a hundred

feet above, the ripping, tearing sound assaulting one’s eardrums, the boys

cheering and tossing their caps in the air.

“Well I’ll

be damned!” Mr Lawless chuckled. “I do believe it’s the Daily Mail

aeroplane!”

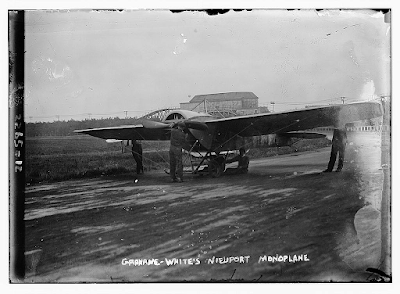

“It must

be,” said Mr Balcombe. “I did hear it might come this way; how splendid! I

suppose that’s that Grahame-White chappie conducting it.” The latter’s hunched

figure was just visible as the aeroplane passed over the Headmaster’s house and

proceeded in the direction of Great Billingham. In the quad a horse neighed and

whinnied between the shafts of the Chaplain’s dogcart and Cook craned her neck

at the sky saying “Well I never! Well I never!” over and over again, twisting

her apron between her hands.

When the

aeroplane was out of sight the two men rounded up their charges and chivvied

them back to the classroom. As they followed the last stragglers across the

terrace, Mr Balcombe said: “I did say I was sure I had met you before you

joined us and now I fancy I know when. Were you ever in the Cape Colony?”

The other

frowned. “Yes. That was some years ago.”

“Indeed.

During the South African War. Were you serving there? I met you, I think, on a

visit to the Second Hampshires.”

“Yes, I

served with them. I remember you now you mention it. We left for the Transvaal about then.”

“How was

the Transvaal?”

“We were

engaged in farm clearances,” said Mr Lawless. He was silent for a moment, then

said: “I resigned my commission not long afterwards.”

“Oh.”

As they

reached the door Mr Lawless paused for a moment, then turned and looked at the

sky. “I wonder, Balcombe. What has just emerged… and what new

beastliness will we commit with the machine we have seen today?”

More flash fiction from Mike:

No comments:

Post a Comment