A tear in the fabric

He was unpopular so they gave him Louise.

“She’s pretty weird,” said his boss, Sam. He was on a

Microsoft Teams call with the Regional Sales Manager.

The latter glared back through the screen, fiddling with the

very small, very expensive earbuds that had arrived that morning and kept

falling out of his ear.

“And he’s so dull I am surprised the clients can bear to see

him,” he replied. “Total nerd. That Dr Who stuff. And his voice. Listening to a sales pitch from

him must be like hearing the Beijing phone directory read by a sedated

sloth.”

|

| Delabane/Creative Commons |

Sam wondered if Beijing had a phone directory, or sloths.

Out loud he said: “Well, maybe they’ll cancel each other out. Either he’ll bore

her to death or she’ll have one of her turns and frighten him to death.”

“With luck,” said the Regional Sales Manager. “In fact she

sounds rather …worrying. Why is she so damned odd?”

“I don’t know,” said Sam. “I think her mother was French.”

“Oh dear. Well, I shall leave it with you.”

He screwed his earbud back in one last time and his image

faded. Sam called Ben in from the outer office.

“We’re giving you Louise for the next few days,” he said.

“Oh,” said Ben. Then: “I think I can manage on my own,

actually.”

“Nonsense. You need a sales engineer with you. Clients

always ask for something to be sorted while you’re there. Let’s go and find

her.”

They saw her from behind, walking up the corridor. Ben

didn’t recognise her; she had recently been transferred from the Darenth

office, having been moved in quick succession from Eastbourne, Sevenoaks and

Tonbridge; strange tales pursued her. She was quite tall, slim, with a long

glossy ponytail of blonde hair, and from behind she looked elegant and rather

graceful.

“I say, Louise!” called Sam. She stopped, and turned, and

Ben took a step backwards, for her eyes were ice-blue, like a glacial lake, and

something turned over in his stomach.

*

BEN put her out of his mind that night. His mum made

spaghetti bolognaise and he always liked it when she did that, and then he

wanted to check and clean his metal detector. He had noticed his route for

tomorrow would take him close to the site of a medieval village and hoped he

might have a spare half-hour. When he had done that, he took Tardis for a walk

then watched the episode of Dr Who he had taped the previous Saturday but could

not make head nor tail of it. “It’s gone all funny, hasn’t it,” said his mum.

“It’s all since they had a black bloke as Dr Who. It’s woke, that’s what it

is.”

“But we don’t really know what colour Dr Who was anyway, do we?” said Ben. “I mean, it’s a bit like Jesus really.” He went out to plug the charger in the car.

The next morning he picked Louise up at seven and they drove

to their nine o’clock appointment in the Midlands. He looked at her from the

corner of his eye and could see no meat-cleaver concealed about her person; she

sat there calmly enough and seemed happy with the morning news on Radio 5 Live.

She even gave a cry of amusement when she saw the little plastic Dalek

stuck to the dashboard. Now and then he ventured a remark and she replied

politely – in fact, she seemed friendly. But she said little.

At length they turned off the A34 and down a broad approach

road to an industrial estate. Ben noticed what looked like a small obelisk at

the entrance.

The call went well enough. Carter & Co Wholesale

Distribution had been happy with their system but now thought it might need

upgrading. Ben and the owner watched as Louise sat down with the IT manager and

went through each gremlin. She treated him with an easy warmth. There was no

sign of oddness. And the client was very happy to be told that they need not

upgrade the system for now and that every issue could be resolved. After a

cordial leavetaking, they drove out towards the access road.

“You seemed to deal with everything in your stride,” said

Ben. “They were very happy.”

“The problems were very simple,” she replied, and laughed.

“They often are with Linux servers. They were just out of space on the disk,

you know! I showed him how to monitor disk usage and clean up outdated files,

logs and data. He just needs to run ‘du’ from the command prompt.”

“You didn’t make it sound that simple,” he said.

“No. There is often something the client should have done

and didn’t but you do not make it sound simple because if you do that you will

make him feel like an idiot.” She thought for a minute. “Especially if it is a

he. Which it often is.” And she looked at him and gave him a brilliant smile.

There’s nothing wrong with this charming woman, he thought.

He steered up the approach road and saw again the small monument, three or four

feet at most; behind it was an area of old decayed concrete, grown with shrubs;

it looked strange in the anodyne estate.

He was about to remark upon it when he heard a terrible

sound, half-scream, half moan; turning, he saw her bent below the level of the

dashboard, her head cradled in her arms. He stopped the car. “Are you all

right? My dear, are you all right?” he asked, then realised that HR might feel ‘my

dear’ was over-familiar. Then she raised her head and he saw that her eyes were

wide and staring with horror and then she started to cry.

“What is wrong? Do you need a doctor?” he asked.

She shook her head several times. “I will be fine,” she

said, and wiped her eyes. “Please do not worry, Ben. This happens to me

sometimes.” Then she said: “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.” And somehow he understood

that she wasn’t talking to him.

*

They drove on. She redid her makeup in the vanity mirror,

and she took a pill. They spoke little. So it’s true, thought Ben; she’s weird.

But by the time they came to the next call she was quite composed, if a little

subdued; and she joined Ben in a discussion with the client on the renewal of

service-level contract, due shortly. He pushed her ‘turn’ out of his mind. They

paused at a Tesco Express to buy lunch; a pasty for him, a plastic bowl of

mozzarella and sun-dried tomatoes for her. They ate in the car park. Two more

calls followed. At four he turned the car for home. The late-summer sky had

darkened, and threatened rain.

“There’s an archaeological site I’d like to have a quick

look at. Can we stop just for a few minutes?” he asked.

“Do you have your metal detector?” she asked. Her face was

rather pale, but she was smiling.

“You know about that?”

“Yes, everyone does, and your collection of Dr Who annuals,”

she said. Her eyes laughed and to his surprise she reached out and touched him

lightly on the arm. “Of course we can stop, Ben. What is the site?”

“It’s probably a medieval village, abandoned in the 14th

century. No-one is quite sure why. Some were deserted because the population

rose very high about then and the soil was exhausted, and then there were the

Acts of Enclosures.” He had relaxed now, his anxiety for her eased; he prattled

on about metal detecting. She listened with evident interest. They drew up in a

small gravel car park with a National Trust sign. Beyond a low earthwork was a

rough pasture with striations just visible in the earth; here and there,

there was a low mound. They were alone. The sky was a livid grey and the air

had become thick and dirty.

They crossed the earthwork and looked around. Louise stood

still and her eyes, opened wide, were strange. Then she closed them, hard; she started

to breathe heavily, swayed and sank to her knees. She gave the eerie

half-scream, half-moan she had made before, then covered her face and bent it

to the earth. Then she brought her head back and cried with fierce pain, and

once again her ice-blue eyes were wide open, staring, and she had gone quite

white. She was sweating, and breathing rapidly.

“Louise! For God’s sake!”

He took her by the arm and raised her up; she took great

lungfuls of air as he dragged her across to the car and eased her back into it,

and then there was a rumble of thunder and the rain started to fall.

She was bent over again. “Pray for them,” she said.

“Please.”

He looked at her then reversed away into the lane. “We’ll

get you a hot drink,” he said, desperate. “There’s that Tesco’s. We can stop

there.”

She nodded. “Don’t be afraid,” she said. “I will be all

right. I will be all right now.” But she was fighting for breath.

He drove the ten minutes or so to Tesco’s, glancing at her

fearfully. Her breathing was still heavy but calmer, and after a few minutes she

sat up straight and clipped her seat belt on; the staring expression had gone and

he felt somehow that she had come back.

The Tesco car park was next to a fuel station beside a busy

main road. It was raining heavily now. He got them cardboard cups of tea with

plenty of sugar. Then he got a blanket from the boot and made her wrap herself

in it and she looked back at him, her face a bit clammy, her hair a little

matted on her forehead, but with the beginnings of a smile.

“What a nice warm blanket,” she said.

“It’s a bit doggy I’m afraid,” he replied. “It’s Tardis’s.”

“Your dog is called Tardis?”

“Well, sometimes he seems to be bigger on the inside than…

Yes, well.” He cleared his throat. “I hope the tea is all right.”

“You’re very English, aren’t you?”

“I suppose I am.” He smiled back, uncertain. “What happened,

Louise? Are you all right?”

“Yes. I am sorry I frightened you,” she said. “Ben, I

wouldn’t bother with Dr Who. Or the metal detector. Other worlds are much

closer than you think. I don’t know what happens. I suppose human distress

burns pockets in the fabric around it and they remain, and sometimes certain of

us, we stumble across them and we can feel, see, another time. Do you

understand?”

He frowned. “What did you see?”

“The people in that village,” she said. “They never left it.

It was the plague. It must have been the Black Death. They were reaching out to

me, crying for me to help, and their limbs were disfigured with terrible black

swellings that bled and suppurated, and these great waves of horror and pain came

over me, and – helplessness – always there’s helplessness, there’s nothing you

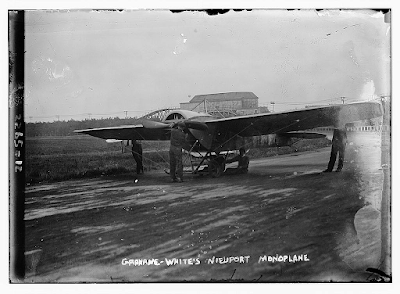

can do. And when we went to Carter’s, I didn’t feel it at first. But it was an

airfield once, wasn’t it? And there was this young man trapped in burning

wreckage and he was screaming to me for help in this mixture of English and I

think it was Polish and he was so young.” She looked up at him, clutching the

blanket around her. “I haven’t told people any of this. They couldn’t take it.

Except one. My mother’s family priest at their village in Normandy. He knew us

all from childhood and he loved us, and he didn’t think I was mad; he did

listen.”

“Well, I suppose the bloke’s in the supernatural business

really, isn’t he,” said Ben, a little at a loss.

She chuckled. “Yes, he knows how to run supernatural server

routines from the command prompt. Doctors were useless.”

“What did he say?”

“That he did not understand God’s purpose but perhaps He had

given me an excess of His compassion, and I must have courage.”

“I suppose that helped a lot, didn’t it,” said Ben with

feeling.

“In a way it did.” She reached out and touched him on the

arm again. “You didn’t think I was mad either, did you? Everyone else does.

That’s why I can’t tell them what happens. But you just seemed frightened for

me.”

“Yes. You don’t seem mad. Yes, I was afraid for you.”

“Maybe that’s because you’re a Whovian,” she said. “Because

that’s weird too. Although it’s sort of nice.”

They were silent for a minute or so, then she said: “This

has been happening to me since I was a child, but it is getting worse. I do not

think I shall survive it.”

It was dusk and raining heavily, and the light was very soft

and grey. He forgot HR guidelines for a moment and reached over to hug her, and

she responded. They stayed together for a minute or two.

Then she said, “You will be late for Dr Who.”

So he drove away. As he steered down the A34, it grew dark. But

now and then they entered a lighted stretch and he glanced to his left and saw

her, exhausted, curled asleep in the blanket; and he felt fear, love and awe.

|

Plague pits, St Catherine's Hill, Hampshire Andy Scott/Creative Commons |

More flash fiction from Mike