On May 11 1875 a girl was born into poverty in rural Michigan. She went on to make her mark on journalism, the cinema and finally in the air. The spectacular, and very American, story of pioneer flyer Harriet Quimby

I’m writing this on Harriet Quimby’s 150th birthday. She was probably born at the family farm in Arcadia, Michigan; we don’t know for certain as the local records were destroyed in a fire not long afterwards. We don’t even know how many siblings she had; there were at least three, and possibly as many as nine, who were stillborn or died in infancy. She never spoke of them. We do know there was one older sister – Kittie, born in 1870 – who did survive to adulthood. But biographers agree about two things.The Quimbys were poor. And William Quimby, her father, failed at everything except marriage.

Born in

upstate New York, William Quimby was from a humble background but married middle-class

Ursula in 1859 when they were both 25. During the Civil War he served in the

188th Infantry Regiment, but his service was undistinguished – he had a

disability that prevented front-line service so served as a cook, but was

invalided out with dysentery. After the war, he was one of the ex-soldiers

who obtained title to land on the frontier on the understanding that he would

clear and farm it within five years. In the Quimbys’ case this was 160 acres at

Arcadia on Lake Erie.

The Quimbys left little record of their lives in Michigan. In later years Harriet would hide her Michigan origins and give her birth date as nine years later, and the place as California. Only in the 1990s did careful research by a local historian, Bonnie Hughes, locate the family farm at Arcadia and establish that they were there when Harriet was born. But we do know, from the diaries and memories of others, what their lives would have been like. According to Quimby’s biographer Don Dahler (Fearless: Harriet Quimby A Life without Limit, 2022), they would have been constantly hungry. Quimby attended a one-room schoolroom. Her mother Ursula was a strong influence. Dahler describes her as “a diminutive force of nature, from an educated and enterprising family …who simply refused to accept the cruel randomness of life.” She supplemented the family income by selling a patent medicine concocted by her father, Quimby’s Liver Invigerator (sic). God knows what was in it. But Ursula would want her daughter to achieve everything she had not.

Harriet was

born in an America that was only just taking shape. In 1875 the United States

wasn’t quite a century old and the Civil War, and slavery, had finished just 10

years earlier. The battles with Native Americans were not yet quite won. Rural

Michigan was, in a sense, on the frontier. Everything was difficult, but as

Quimby was to prove, nothing was impossible. The story of Harriet Quimby was to

be a very American one indeed.

*

Sometime in

the 1880s (some sources say 1884, others after 1887), the family gave up on the

farm and headed west in search of a better life. They settled in Arroyo Grande,

between San Francisco and Los Angeles.

William Quimby worked at odd jobs with limited success and Ursula eventually sent him off up the Pacific seaboard to sell Liver Invigerator. Meanwhile some point soon after their arrival in California older sister Kittie, still a teenager, eloped. Neither Harriet nor her parents ever spoke of her again. Dahler says an 1898 pension application completed by William Quimby gives her married name (Rasmussen) and states that she lived in Oakland. But no-one knows what became of her. Meanwhile the family continued to struggle; the 1890s were a depressed time and many Americans were out of work. Sometime around 1900 they wound up in San Francisco. Leslie Kerr, in her biography Harriet Quimby: Flying Fair Lady (2016), says they were living in what was basically a hovel. Dahler says it was a one-room apartment in Montgomery Street, near Chinatown and the red-light district. But Harriet did finish high school. After that she worked as a clerk.

She had

grown up to be a young woman of quite startling beauty, tall and slim with dark

hair and, according to one source, striking green eyes (others say grey or

blue). And she was starting to meet people. At night, she started moonlighting in the

theatre, wanting to be an actress. She got mixed up in the Bohemian Club, still

a famous San Francisco institution; it had been founded in 1872 and early

members had included Jack London, Mark Twain and Ambrose Bierce. We don’t know

who she knew there, but it seems likely she was at least acquainted with London

and Bierce. We do know she knew the German-born photographer Arnold Genthe, who

would become famous for his shots of San Francisco in the aftermath of the 1906

earthquake. Both Dahler and Kerr say that Genthe shot a nude photo of her that

hung behind the bar at the club until the latter was destroyed in the San

Francisco Earthquake in 1906.

Kerr goes farther, reproducing an early-colour autochrome of a beautiful young nude that she says is the portrait. It may be, but maybe not. The Library of Congress, which has it now, does attribute it to Genthe but doesn’t identify it as her. Genthe started experimenting with the autochrome process in 1905, by which time Harriet had already left San Francisco. The Library of Congress dates it to after 1911. In that year Genthe himself moved to in New York but Quimby was by then quite well known, and it seems unlikely she would have posed nude then. But Quimby did pose for him, for publicity shots for a 1900 production of Romeo and Juliet she mounted with her friend Linda Arvidson. The latter later wrote in her own book, When the Movies were Young, that he did them for free because of her beauty. Whoever the woman in the mysterious autochrome is, she is lovely. And it does look like her.

The play

was a bold move and got some kind reviews, but did not lead anywhere. Dahler

says that Quimby herself decided that she wasn’t a very good actress and should

try journalism instead. According to Kerr, Ursula had wanted her to do that

anyway. Meanwhile the Invigerator had paid for some nice clothes, so Ursula had

chopped some years off Harriet’s age and invented a past for her of private

tutors in Europe for her. For her husband, she concocted a past in the US

consular service.

I wonder if

Harriet really needed that sort of help. To get into journalism, she did what

she was always to do in her short life; she kicked down the front door. She

walked into the office of Will Irwin, editor of the San Francisco Call (he

almost certainly knew her from the Bohemian Club). He gave her a try and in

October 1901 her first piece appeared, a description of the artists’ colony in

Monterey. It was rather good. It seems she really did have a flair for ‘slice

of life’ stories; moreover she went out and got her copy in person. This description

of a trip on a fishing boat had meant a 2am start; it was published only a week

or two after her first meeting with Irwin:

Have you

ever heard orders given from hurried men in Italian-French-American? If not you

have missed a treat for those sons of the seas all have musical voices, strange

to say. …As it neared the noon hour everybody found a comfortable seat and

waited for “breakfast”; did not wait very patiently either for the salty air

gives one a royal appetite. Great round loaves of bread were brought out and

…Upon them, about an inch thick, were placed good-sized rounds of beefsteak.

Harriet

Quimby realised she was a good journalist. She never looked back, and in

January 1903 she decided to try her luck in New York.

*

Quimby’s

biographers describe, in some detail, what her arrival in New York would have

been like, but both are using their imagination – in reality, they can’t know.

Kerr has her arriving at Penn Station in the snow, and making her way to a

hotel, where she is looked at with a certain suspicion. Dahler has her arriving

in Manhattan by ferry and disembarking at the 23rd St ferry terminal. Kerr’s

version sounds more likely, but from something Quimby later wrote it seems

Dahler is right. It’s all part of the challenge they have writing about Quimby;

she left plenty of good journalism, but no personal correspondence. Neither did

she live to write an autobiography. One suspects that had she done so, it would

have been rather good – but would have left out a lot; as we’ve seen, she and

her mother were not frank about their past.

What we do

know is that she once again kicked the front door down, but with charm. She

called on John Foster, editor of Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly. Founded by

Frank Leslie in 1855, it was no longer run by the family but had retained the

name, and was an important weekly news magazine with a circulation of probably

60-70,000. Foster was not, at first, very friendly but agreed to give her a

try; her first piece, about Chinatown, impressed him and from then on she

worked for the paper.

In 1906 she

decided she wanted to be a theatre critic as well, so went to the theatre,

wrote a review and got the job. She would be quite influential in this role. She

could be quite a rough critic; she was also a witty one and some of her

barbs must have hurt. Kerr quotes one review as follows: “The production of The

Foolish Virgin fell as flat as an overdone omelette souffle. The same may

be said of the acting of Mrs. Campbell, who, in my opinion, has been highly

overrated.” Ouch.

|

| Blink and you'll miss her: Quimby in Lines of White on a Sullen Sea (1909) |

But there

seems also to have been some campaigning journalism. Quimby was not the first

American woman investigative reporter; Ida Tarbell had recently published

damaging revelations about Standard Oil, and 20 years earlier Nellie Bly had famously

gone undercover to expose conditions at the insane asylum on Roosevelt Island.

But Quimby did write of social matters – including an investigation into

prostitution, an article that caused quite a bit of trouble at the time. What

she did not do was campaign directly for women’s equality. She did say that she

was in favour of women’s suffrage (although she contradicted herself on this

later). But in the main this was something she avoided. Whether this was

because she was not committed, or because it was a bad career move to get

involved, is not clear.

By now

quite successful, Quimby was able to bring her parents from San Francisco. She

was also able to give friends a helping hand. In April 1906 the San Francisco

earthquake devastated the city and Quimby’s friend Linda Arvidson and her fiancé,

also an actor, found themselves homeless. They decided also to try their luck

in New York. Not all went well at first; Arvidson would later remember an

occasion when Quimby came to see how they were doing. She was very well-dressed

and on her way to a social occasion by the sea, and the contrast upset

Arvidson’s fiancé, by then her husband. He in the meantime had been forced to

get bit parts working for the Biograph Company, a movie maker – at that time

actors did not regard this embryonic industry as respectable. But it caught his

imagination. The Biograph Company gave him a chance to move behind the camera.

His name was D.W. Griffith.

Between

1908 and 1911 he directed an enormous number of short films for Biograph, and

seven of them were scripted for him by Harriet Quimby. They were silent, with

almost no dialogue, and her scripts are perhaps better described as film

treatments. In Harriet Quimby – Flying Fair Lady, Leslie Kerr reproduces

the handbills for all seven; these would have been distributed, presumably, to

cinema managers and include an order number for each production. They give a

detailed description of the plot. Given that Quimby was very beautiful, you

wonder at once whether she was ever tempted to move in front of the camera. Her

biographers suggest she did appear in a 1911 D.W. Griffith film that she had

scripted for him, Fisher Folks. But she doesn’t appear in the cast

lists, even as one of the 11 known extras.

Oddly,

neither Dahler nor Kerr mention another Griffith film for Biograph in which she

is known to appear very briefly, though she didn’t write it. It is Lines

of White on a Sullen Sea (1909), which like Fisher Folks is a

romance set in an imaginary fishing community. Blink and you will miss her, but

she is there. She was in good company, as at least two other extras in the film

would go on to bigger parts: Mary Pickford and Mack Sennett. The film can be

streamed on the website of the Library of Congress. It has been said that

Quimby was romantically involved with Griffith, and he and Arvidson did

separate in 1912 (though they did not divorce until 1937). But the only real

evidence, apart from rumours at the time, is a scarab ring that Griffith wore

that Quimby gave him.

The ring had been bought in Egypt. In 1907 Quimby went there and to Palestine via London, Ireland and various places in Europe that she toured by car. She had already been to Cuba in 1906. Other destinations included St Thomas, Panama and Trinidad. She wrote pieces for Leslie’s – but did not just write. Genthe may or may not have taken a nude portrait of Quimby but he did teach her photography. It is hard to find her pictures now, but some were published in a series of compilations by Leslie’s journalist John Schleicher called Around the World with a Camera; the first came out in 1910 and includes quite a number of photos by Quimby – again, Leslie Kerr has managed to find them and includes some in her book. These show Quimby was an at least competent photographer, and maybe a very good one.

|

| Some of Quimby's photographs from the Caribbean in 1906 or 1907,reproduced in Around the World with a Camera in 1910 |

Journalist,

critic, screenwriter, photographer; even, perhaps, actress – there seems no end

to what this dazzling woman could do. But in the end, she would fly too close

to the sun.

*

Motoring

was in its infancy in the 1900s but Harriet Quimby had Mr Toad tendencies early

on. Kerr suggests that she was the first woman in the States to get a driving

licence and to buy her own car. I doubt if either is true; the first is sometimes

attributed to Anne Rainsford French in 1900. In any case, many states did not

require a licence to drive until long after Quimby’s death, and in the early

years many issued them solely for identification; they did not require a test. Dahler

suggests she had had a car of her own, a yellow convertible, as early as her

San Francisco days. That seems surprising, given that the family was struggling

and in 1903 cars were still very rare. Kerr says Quimby acquired her first car,

and her licence, in New York in October 1908.

We do know

that in 1906 she went for a ride out on Long Island with the racing driver

Herbert Lytle, who was practicing for the Vanderbilt Cup driving a Pope-Toledo (he

didn’t qualify that year). They reached speeds of 70MPH and Quimby lost her

hat. But she clearly enjoyed herself, as her report in Leslie’s confirms:

You feel the swift currents of

air produced by the mad flight of the machine... A curve and a sharp angle …and

the car careens virtually on one wheel, and the whole machine seems lifted up

in the air and comes down to earth again with a jump. …You think, if indeed you

think at all, that if it goes much faster you will topple right over, but soon

you begin to slow down, seventy, sixty, fifty. Why you seem to actually crawl

along at fifty an hour, and although every nerve in your body is quivering and

you have just enough strength to hang on to the strap, you manage to shout an

answer to Lytle, who asks with exquisite sarcasm, at the top of his voice,

"Was that fast enough?" and you enjoy the satisfaction of seeing him

nearly fall over with surprise as you fire back "Twasn't very fast; can't

you make one hundred and twenty?"

|

| October 1908: With Herbert Lytle, the Pope-Toledo, and still (for the moment) with hat |

But then

Quimby became interested in aviation.

The first

significant airshow in America took place at Dominguez Field near Los Angeles

in January 1910, and Dahler thinks she was there, maybe with a feature article

in mind. The second such meeting was the Harvard-Boston meet in September, and

at least one source thinks this gave Quimby the flying bug, but we don’t know

if she went. However, the third major American airshow of the year was on a

racetrack at Belmont Park, Long Island, in the last week of October. And this

time we do know Quimby was there.

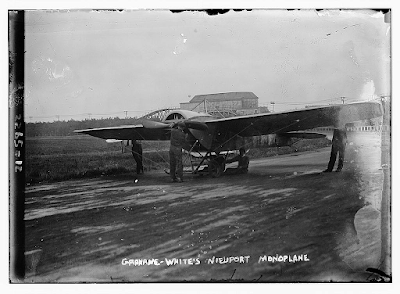

The

contestants in the competitions at Belmont included some of the best pilots of

the day, including America’s Glen Curtiss, France’s Roland Garros and Britain’s

Claude Grahame-White. They also included a colourful American called John

Moisant. His family, French-Canadian in origin, had settled in Illinois, where

he was born in 1868. In the 1890s Moisant and his brothers moved to El Salvador

to open a plantation. Moisant tried to overthrow the government in El Salvador

twice, with some loss of life. He had eventually been told to back off by the

US government, which was finding him a nuisance. Back in the States he read

about the new science of aviation and wondered if planes might come in handy

for coup attempts, so went to France to learn to fly. After a slightly farcical

attempt to build and fly his own plane, he sensibly got Louis Blériot’s

aviation school to teach him. He became so enamoured of flying that he lost

interest in coups; this was a more interesting hobby. On his return to the

States he started to build monoplanes of his own based on Blériot’s designs. At

Belmont he won an important trophy against strong competition from

Grahame-White.

Quimby was

among the spectators. Exactly what took her there is not clear. Some accounts,

including Kerr’s, say that she went there with her friend Matilde Moisant,

John’s younger sister. Quimby and Matilde Moisant did become friends later but

Dahler’s account suggests that Quimby may not have known her at that stage; she

went alone and, fascinated by what she saw, decided she must learn to fly and

that Moisant was going to teach her. If Dahler is right, she then found out

where the Moisant family were dining that night and did what she did best –

kick down the front door, but with charm; she marched up to their table and

told John Moisant that he must teach her to fly.

|

| Matilde Moisant in 1911 or 1912 |

Not all early aviators approved of women flying. The Wright Brothers would not teach women and they were not alone. But John Moisant and his elder brother Alfred were planning to open a flying school and, perhaps surprisingly, Moisant agreed there and then that she would teach her. At this point Matilde Moisant seems to have decided he would teach her to fly as well. Moisant insisted that they wait until the spring when the weather in the northern US was suitable. In the meantime John Moisant would be travelling the warmer States for the winter, giving lucrative flying displays.

He did not

return; on New Year’s Eve he was flying for a crowd near New Orleans when he

was caught by a gust of wind and thrown from his aircraft. He survived the

impact and was taken to hospital, but was pronounced dead on arrival.

*

Harriet

Quimby was not put off. More surprising, neither was Moisant’s sister Matilde. After

some thought, Alfred Moisant proceeded with the flying school, and that spring

the two women began to fly, Quimby driving out to Long Island in the very early

hours to begin lessons at 4.30am. They were taught by André Houpert, a

Frenchman who had himself qualified in France just the year before (at the time

France was the world’s leader in aviation, and the best pilots often were

French). Dahler and Kerr both say she snuck off in the early morning so that

no-one would find out that Leslie’s most glamorous reporter was learning

to fly. But I suspect she (and Leslie’s, which had paid for the lessons)

always meant it to leak and of course it did, with Quimby being spotted by a reporter from the New York Times.

In due

course Houpert decided she and Moisant should be tested for their pilot’s

licences. The Aero Club of America was not keen on testing women but were

eventually persuaded, and on August 1st she passed. Unfortunately another

candidate then damaged the plane, delaying Matilde’s test for 14 days; but she

too then passed with flying colours. Quimby was the first American woman to

obtain her licence, and only the seventh in the world; the first had been

Raymonde de Laroche in France the previous year.

This should

be put in context. The US didn’t actually require pilot’s licences until 1928; the Aero Club of America issued Quimby and Moisant’s licences on behalf of the

Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. In the meantime, at least a few women flew

anyway. Blanche Stuart Scott, then the best-known, and perhaps the first, American woman flyer, never bothered to get a licence. This had not stopped her

thrilling spectators by diving steeply from 4,000ft and pulling out 200ft from the

ground. (Despite this, she lived until 1970.) Even so,

Quimby was the first American woman to gain an internationally recognised

pilot’s qualification.

|

| Quimby poses with one of the Moisant monoplanes in 1911, probably at an aviation meet on Staten Island in September but possibly in Mexico later that year |

The next

step was to make money out of it. The girl from the hardscrabble farm never did

feel secure, and she wished to provide for her parents. She went exhibition

flying. Blanche Stuart Scott already did this, working first for Glenn Curtiss

and then for Glenn Martin. Quimby teamed up with the Moisants. Soon afterwards

the family were invited to hold flying exhibitions in Mexico, to introduce

Mexicans to aviation and to celebrate the inauguration of President Francisco

Madero. In November 1911 Moisant’s flying circus arrived in Mexico City. It

included André Houpert, Roland Garros, Matilde Moisant and Quimby. Houpert

became the first man to fly over Mexico City; Quimby, the first woman.

Meanwhile Matilde Moisant decided to love-bomb the new President by dropping

flowers for him on the Chapultepec Palace. The two women also delighted a crowd

by flying over the city side-by-side.

And then

Quimby bailed out of the whole enterprise. She did not say why. In fact she had

her eyes on a bigger prize: First woman across the English Channel, and was

afraid someone else would beat her. She slipped away from Mexico, where things

were about to go wrong – Madero faced an armed insurrection led by Emiliano

Zapata and the rest of the aviators, caught up in the chaos that followed, were

lucky to get away in one piece.

How Matilde

Moisant felt about this is not clear; it is said her enthusiasm for flying

faded somewhat after her friend’s defection. Besides, she had lost her brother

– and had had various near misses of her own. “The earth is bound to get us

after a while,” she said later. “So I shall give up flying before I follow my

brother.” She decided to bow out with a final exhibition in Wichita Falls,

Texas on April 13 1912. The following day the crowds rushed the field, forcing

her to crash-land. The aircraft exploded and caught fire but Houpert and

another man dragged her from the flames without serious injury.

Moisant was

just five feet tall, slim, energetic, and if pictures are to be believed, madly

attractive with a direct gaze and a cheeky smile. She may also have been an

even better flyer than Quimby (Houpert considered her a natural pilot). She did

not return to flying and died in 1964.

Also left

behind was André Houpert. He, like Griffith, is said to have been Quimby’s

lover. Apparently the Houpert family did later believe this, but the only real

evidence is a locket Quimby gave her with her picture. It was dated August

1911, which is the month Quimby passed her FAI licence examination; it could be

a love token but could also simply be in thanks for Houpert’s training. If

there was a romance, Houpert never spoke of it. He died in New York in 1963.

*

In any

case, Quimby had moved on. On Sunday, April 14 1912 – the day on which Matilde

was dragged from her burning plane – she was in England. To be precise, she was on the ground near Dover with one

A.L. Stevens.

The latter

was a pioneer balloonist and had also developed the manual parachute. His

ballooning escapades had included landing on the spire of Notre Dame Cathedral

in Montreal and landing in the Atlantic. He was born in Cleveland but no-one

seems quite sure when – in 1912 he was probably 41. His name at birth was

probably not Stevens (his parents were Czech). He had become Quimby’s business

manager. He is also said to have been her lover, though again there is no proof

– and he was in fact married, though his wife divorced him in 1921. Whatever he

was to Quimby, he had helped her in her negotiations with Louis Blériot, who

had agreed to lend her a plane on the understanding that she would order one of

her own. He also helped her secure a sponsorship deal with the Daily Mirror.

|

| Quimby in her Blériot about the time of her Channel flight |

And the

weather on that Sunday was ideal. But Quimby refused to go. She always refused

to fly on a Sunday. This may have been for her parents, but perhaps she herself

was superstitious. She carried charms for luck (though other flyers, including

Matilde, also did this). She also had an odd fear that her body might be used

for medical research after her death, and had left instructions for it to be

protected from grave-robbers.

For

whatever reason, the day passed and with it the weather; Monday was awful.

Tuesday April 16, however, was just good enough. At 5.30am, she went.

Henry

Holden, in Her Mentor was an Albatross (1993), quotes her as saying: “I

started climbing steadily in a long circle, and soon reached an altitude of

1,500ft. As I looked down, Dover Castle was in a veil of mist. I could barely

see the tugboat filled with reporters sent out by the Mirror… The fog

quickly surrounded me like a cold, wet, gray blanket.” The mist made it hard to

see: “I had to push my goggles up to my forehead. I could not see through them.

I was traveling at a mile a minute and the mist felt like tiny needles on my

skin.” She could see very little - but she had with her a compass. She had

never had one before but an English flyer, Gustav Hamel, had given it to her

and insisted that she use it. It would have been easy to become disoriented and

be lost at sea; it had happened to others. Hamel himself would be lost flying

the same route two years later.

Somewhere around mid-Channel, her nerves torn by the fog, she suffered a near engine failure, but was able to restart the three-cylinder Gnome radial engine and in due course saw the vague outline of the French coast. “It was all tilled land below me, and rather than tear up the farmers’ fields, I decided to drop down on the hard and sandy beach. I did so at once, making an easy landing.” She had landed not at Calais as intended but 30 miles (about 50km) away at Hardelot, oddly enough where Blériot had his own base. She received a warm welcome from the fishing community, who quickly manhandled her plane up the beach to protect it from the rising tide. She sent a telegram to Calais, where the Mirror reporters and photographers were waiting; they arrived quickly, with a bottle of champagne.

The

champagne soon went flat. The Daily Mirror had promised her $5,000 for

her story after the Channel flight but went back on its word when another woman

made the crossing two days earlier, albeit only as a passenger (flown in fact

by Hamel). Moreover the Sunday when Quimby should have flown was, it turned

out, the day the Titanic hit the iceberg; the two days’ delay meant the

news had broken and she was not on the front pages. The Mirror’s own

report the day after her crossing was relegated to two columns on page eight.

Quimby

returned to the States and took delivery of the plane she had ordered from Blériot

– a Type XI-2 “Artillerie”, a two-seater designed for possible military use.

Stevens managed to get her a few deals for exhibition flights, paying $1,000 or

more – a huge sum in 1912. They also clinched a sponsorship deal for a popular

soft drink, Vin Fiz, a grape soda that happened to match Quimby’s famous purple

flying suit. One journalist, says Dahl, described it as “a cross between river

water and horse slop”. Still, business was good. The press, charmed by her pale

skin and delicate beauty, dubbed her “the Dresden China aviatrix”.

But she may

not have enjoyed it. Exhibition flying was a ruthless business and despite the

high fees, the cost of mechanics and transport for the aircraft ate into

profits. Henry Holden quotes Houpert as saying that Quimby had become less

enthusiastic about flying. She still needed the money; she had to take care of

her parents. But she seems to have told friends that she intended to give it up

when she could, and pursue a dream of writing a novel. She may also have

realised, as Matilde Moisant had, that the earth was bound to get her after a

while. In fact she may have been in a thoughtful mood when she arrived for the

Boston Air Meet at Squantum, Massachusetts.

On July 1

she made a number of flights at the meet and at 6pm, after competitive flying

had finished for the day, she took the meet organiser, William Willard, for a

flight across the harbour and around the Boston Light. As she descended towards

the landing strip on her way back, the Blériot’s nose pitched downward and

Willard was thrown out. Quimby appeared to be fighting to bring the nose up but

was herself thrown out after Willard. They fell into the mud flats at the edge

of the harbour. Both died at once. There is a poignant photo of Quimby’s body

in its stylish flying suit, slung across the shoulders of the man who is

carrying her to the shore.

*

Harriet

Quimby lived a very public life. But she left no correspondence, and never

talked of private matters. We don’t know who Quimby’s lovers were (at least,

not for certain). We're not even sure how many siblings she had.

That was not an accident. In 1907 she had interviewed Rose Stahl, an actress of

some years’ standing who had just broken through in a big way in a play called The

Chorus Lady. Stahl gave Quimby a piece of advice – to keep her private life

just that: “The less the public knows of your private life the better it likes

you.” It was advice she clearly did not forget. All we really know is that she

was intelligent, confident and charming. She was also probably rather decent; she

seems to have had no known enemies and some good friends.

|

| Quimby (left) with Matilde Moisant |

And she was

very beautiful. Her pictures confirm this. Matilde Moisant would later recall

her as “tall and willowy…the prettiest girl I’d ever seen. She had the most

beautiful blue eyes, oh what eyes she had.” Perhaps that is what makes her

story so resonant today; her charm and her beauty, combined with her awful

sudden death.

But there was something else too. Quimby was born on the American frontier, in a country that was less than 100 years old, to a father who was a veteran of the Civil War. She was also born into poverty on a hardscrabble farm. She could have lived and died that way, but decided she wouldn’t. All her life, she lived her own life and no-one else’s. If she wanted something, she kicked the front door down. To be sure, she did it with charm. But she did it. Nothing was impossible. Harriet Quimby’s story is about as American as it is possible to be.

Mike Robbins's book On the Rim of the Sea is available as a paperback or ebook. More details here. Follow Mike on Bluesky or X or browse his books here.