Crime writing is

fun, but don’t give up the day job... A look at two vintage detective stories by men who

didn’t

When I was a child my

parents used to like a good thriller or crime story on TV, especially on a

winter’s night. “See what’s on tonight?” my mother would say, as my father

dutifully opened The Times at the telly page; and then she would almost

always, say, “I do hope there’s a good murder.” Back then, that meant a

series such as The Saint, adapted from the stories of Leslie Charteris

and starring Roger Moore, then in his 30s. Or, a little later, The Expert,

in which Marius Goring played a forensic pathologist. There were many more,

including the odd American import.

Like my mum, I do enjoy

a good murder. Committing one oneself means lots of messy paperwork and there

are ethical questions, so I prefer to read a good crime novel. A year or so ago

I wrote a piece about the Golden Age of Crime, focused on the

four famous Queens of Crime – Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Margery

Allingham and Ngaio Marsh. But I mentioned that there were a host of others, often

now forgotten – some with good reason, but others still well worth the read. A

recent rummage round a Norwich bookshop (The City Bookshop, since you ask;

others are available) turned up a selection. Some had been ‘rediscovered’ and

put out under a modern imprint, but one of those was very disappointing; I

could not read more than 20 pages. However, there were also some original

Penguins in their green-and-white covers, very old, very pre-loved and in one

case stuck together with Sellotape. These proved rewarding.

Like my mum, I do enjoy

a good murder. Committing one oneself means lots of messy paperwork and there

are ethical questions, so I prefer to read a good crime novel. A year or so ago

I wrote a piece about the Golden Age of Crime, focused on the

four famous Queens of Crime – Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Margery

Allingham and Ngaio Marsh. But I mentioned that there were a host of others, often

now forgotten – some with good reason, but others still well worth the read. A

recent rummage round a Norwich bookshop (The City Bookshop, since you ask;

others are available) turned up a selection. Some had been ‘rediscovered’ and

put out under a modern imprint, but one of those was very disappointing; I

could not read more than 20 pages. However, there were also some original

Penguins in their green-and-white covers, very old, very pre-loved and in one

case stuck together with Sellotape. These proved rewarding.

First, A Question of

Proof by Nicholas Blake.

*

A Question of Proof is a classic Golden Age of Crime

story. If you like Agatha Christie & Co., you may well enjoy this.

Written in 1935, it is

set in an English prep school. It’s summer and the school’s Sports Day has

rolled around. Sometime between lunch and tea, one of the pupils, a ghastly

little tick called Algernon Wyvern-Wemyss, meets with a most unfortunate end.

Suspicion rests on the members of the staff common-room. Was it Evans, who is

carrying on with the headmaster’s wife, and may have been blackmailed by the

boy? Wrench, who is doing likewise with one of the maids? Either could be

ruined if rumbled (this is the 1930s). Or was it Gadsby, the prodigious

drinker? Or Sims, who cannot keep order? Evans’s eccentric friend Nigel Strangeways

is brought in to find out.

It’s the first of many

outings for Strangeways, who was to feature in most of Nicholas Blake’s

detective novels, of which there were 20 in all. As many people will know,

“Nicholas Blake” was a pseudonym for C. Day Lewis; the future poet laureate was

himself an impoverished prep-school schoolmaster at the time and wanted to earn

some money from detective fiction without risking his reputation as a poet. He

proved quite successful; the books were never quite as popular as (say) Agatha

Christie’s, but they did do well and are still read.

It’s easy to see why. A

Question of Proof seems a bit old-fashioned now, but it’s well-written and

well-paced and the characters very well-drawn. And having gone to a prep school

myself, I think he catches the atmosphere. No-one mourns the dead pupil; for

the other boys, his sudden death is the occasion not for sadness but for

excitement and speculation, and Day Lewis catches this callousness rather well.

The chaos in Sims’s classroom is realistic; there were always teachers like

that who could not control their pupils. There’s also a surprising whiff of

radical politics, though it’s very subtle – Day Lewis was on the left most of

his life and at the time this was written was actually a member of the

Communist Party. One wonders how he really felt about teaching in a place like

this.

|

C. Day Lewis in 1936 (Howard Coster/

National Portrait Gallery) |

I am not sure how I feel

about Strangeways. He is somewhat contrived, with his carefully crafted

eccentricities such as an addiction to tea, in huge quantities, throughout the

day – though some people do have that in real life (the late Tony Benn was an

example). Still, most writers of detective fiction have such a lead character,

a cipher through which the reader follows the crime being solved. They are

often given an odd backstory or a pattern of eccentric behaviour, and this is

consistent from one book to another. That consistency means readers know what

to expect, and will buy the book. Christie of course had Poirot; Sayers had

Lord Peter Wimsey; P.D. James had Adam Dalgleish. But the writer must ensure

that their investigator acts true to character, and that – especially in later

books – their eccentricities do not become so hackneyed that they become a

caricature of themselves.

A number of “Nicholas

Blake’s” detective novels are still in print, including at least three or four

for Kindle. A Question of Proof, the first, was published in 1935 and

the last, The Private Wound, as late as 1968. By then Lewis was Poet

Laureate, having been appointed at the start of the year. It is one of four

“Nicholas Blake” novels that doesn’t feature Nigel Strangeways. The other 16

do.

Detective fiction does

seem an odd departure for an intellectual like Lewis. At the time A Question

of Proof came out he was 31 and had published his first collection of

poetry 10 years earlier; he was an associate of W. H. Auden and was strongly

influenced by him as a poet. (Nigel Strangeways is said to have initially been

modelled on Auden, though he acquired a more distinct character in later

books.) Patrick Maume, writing in the Irish Dictionary of National Biography,

says that Day Lewis had reviewed numerous detective stories for the Spectator

and thought he might as well have a go himself. It is also said Day Lewis

needed the money. Whatever his motives, the identity of “Nicholas Blake” soon

became known; the board of Cheltenham College, where he was teaching, were

concerned and he had to assure them A Question of Proof was in no way

autobiographical. (The board were already displeased by his membership of the

Communist Party.)

As to the Blake novels

themselves, it may seem that they were meant purely as entertainments but this

was not entirely so. “Day Lewis always made it clear that he did not regard the

Nicholas Blake novels as serious works of art, but that they should not be

dismissed as purely commercial,” says Maume, adding that Day Lewis used the

books to explore certain morbid psychological states. There are also political

overtones; The Smiler With the Knife (1939) revolves around a fascist

conspiracy, very topical at the time. Maume says the film rights were optioned

by Orson Welles. Moreover crime fiction might have been a sideline for Day

Lewis, but it was a jolly successful one. One of the novels, The Beast Must

Die (1938), sold some 430,000 copies, according to Maume. It was filmed in

1969 by Claude Chabrol, and is still in print.

*

During the war Day Lewis

was in a long and troubled affair with the writer Rosamond Lehmann. He was thus

a frequent visitor to her cottage at Aldworth, on the Berkshire Downs west of

Reading. There he will have become acquainted with the journalist Anne Scott-James

– then women’s editor of Picture Post – who owned the cottage next door.

He will thus also have known Scott-James’s then husband, Macdonald Hastings,

who also worked for Picture Post, in his case as a war correspondent. After

the war he too decided to try his hand at crime fiction. Cork and the Serpent (1955) was one of

several detective novels he produced between 1951 and 1966.

However, it turns out

that not one but two clients have reported it as such. So whose was it? One of

the two is clearly lying. The eccentric playboy Maharaja of Lumphur? Or the

Berkshire racehorse owner and peer Lord Pangbourne? Before Cork can dig

further, something most regrettable happens to the Maharaja. Cork decides to

speak to Pangbourne and glides off down the Great West Road in his Bentley. The

action takes place mainly on the Berkshire chalk downs that to this day are an

important centre for the horse-racing industry. The world of horse racing is an

important backdrop to the story, as are the rural locations.

It all sounds a bit

genteel. It isn’t; the folks in this book do some quite unpleasant things to

each other, there are well-drawn, colourful characters and, as in all the best

detective yarns, you do become invested in the story and want to guess who the

villain is before Cork does. There is also a surprising final scene involving a

Royal garden party. Now and then the plot does get contorted, and it was never

quite clear to me exactly how the streetwalker, Carmel, came by the brooch. But

it’s all good fun. Moreover Hastings’s depiction of Carmel and of the Indian

characters seems old-fashioned today but was probably liberal for its time

(although Macdonald Hastings himself was not; he held very conservative views).

The rural and racing

themes are not surprising, as author Hastings was a great lover of country life

and of country sports. According to his son, the journalist and historian Sir Max

Hastings, he spent a great deal more than he could afford on the latter,

keeping a collection of superb shotguns. He had been quite a distinguished war

correspondent; his more dangerous assignments included trips on motor torpedo

boats and a bombing raid over Germany in a Short Stirling, the crew of which

were killed the following night. His son wrote in a family memoir (Did You

Really Shoot the Television?, published in 2010) that he was probably quite

reckless. After the war he edited the prestigious Strand Magazine, and

when that folded in 1950 he started a magazine on the countryside and country

pursuits, Country Fair (this too lost money). It was about the same time that he started

writing detective novels. His character, Montague Cork, was based on a real

insurance magnate who Hastings knew, Claude Wilson, head of the Cornhill

Insurance Company. History seems to record little of Wilson, and Hastings

himself once said that nothing so exciting had happened to Wilson in real life.

There were five Montague

Cork novels. In Sir Max’s view, Cork and the Serpent is actually the

weakest of them; it draws on Hastings’s knowledge of racing, which was not as

great as he supposed it to be, according to Sir Max. Neither, he adds, was his

father really familiar with the aristocracy, and this also shows. Critic Daniel

P. King, writing in Twentieth Century Crime & Mystery Writers

(1980), calls it a “slow moving tale with much muddling about”. He also states

that the Cork novels “range from the trite to the noble”. This might be

sweeping. To be sure, Macdonald Hastings was not Agatha Christie or Dorothy

Sayers. Detective novels, for him, were a sideline in a busy life. Still, the

Cork books sold well; and I thought Cork and the Serpent much better

than King judged it to be. If it is the weakest, then the others might be well

worth reading.

In Did You Really

Shoot the Television?, Sir Max is often highly critical of his father, who

was bad with money, had very right-wing views and was monumentally tactless.

But he had a varied and successful career in journalism, and later in

broadcasting. And Montague Cork, says

Sir Max, was a “delightfully original fictional creation”; he praises, too, the

countryside descriptions in the books, especially in Cork on the Water

and Cork in Bottle. I would like to read the rest.

Not all vintage crime

fiction is worth reading. Although some books are unjustly neglected, others

are neglected all too justly. But Nigel Strangeways and Montague Cork do

deserve our time. As it happens, both were written by men who had remarkable lives

of which crime fiction was but one part. So if, as crime writers, both are

still worth reading, maybe that is not a coincidence.

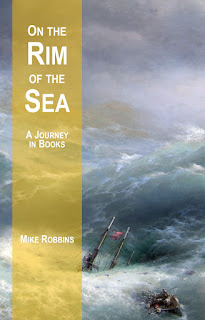

Mike Robbins’s latest book, On the Rim of the Sea, is now

available as a paperback or ebook. More details here.